Banks fear the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s debt-collection proposal could unfairly put them in the agency’s firing line, inflate compliance costs and invite lawsuits from states and consumers that lenders fought for years to block.

At issue is whether commercial banks would be subject to the plan, which is an effort to modernize federal protections for borrowers from harassment by third-party debt collectors.

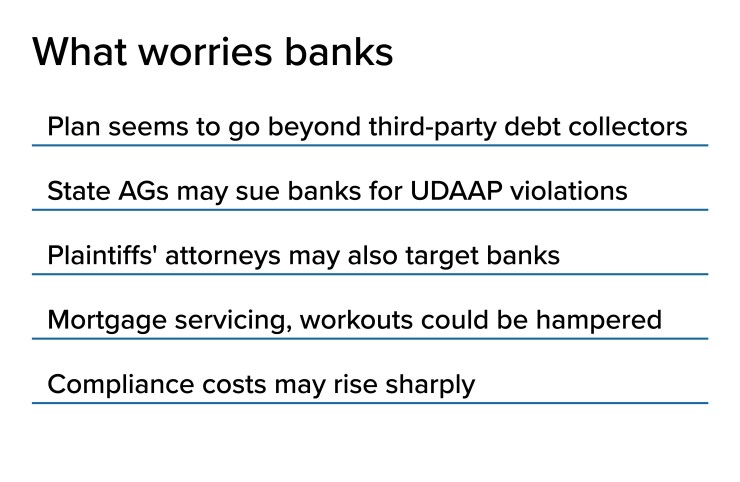

Banks argue that, since they own the credits they collect on, the final rule should not apply to them. However, industry lawyers warn that the CFPB’s proposal is written so broadly that it would ensnare banks, too.

“The proposal will introduce substantial uncertainty and legal risk for first-party creditors” like banks, Diana Banks, senior counsel for fair and responsible banking at the American Bankers Association, wrote in a comment letter to the bureau.

“Congress intended that" the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act of 1977 "would establish protections against unscrupulous third-party debt collectors,” Banks said. “Congress did not intend, nor did it design, the FDCPA to regulate the practices of first-party creditors.”

A major problem, according to the banking industry, is that the CFPB’s proposal would inappropriately draw authority from legal provisions affecting banks, specifically the prohibition of unfair, deceptive or abusive acts or practices (UDAAP) codified in the Dodd-Frank Act.

It would create a kind of legal exposure that banks thought had been eliminated in

Banks fought for 30 years for that clarification, and now the CFPB seems to be ignoring that ruling, Debra Stamper, general counsel at the Kentucky Bankers Association, wrote in a comment letter on the CFPB proposal.

“Rather than incorporate the clarifications from the Supreme Court … the [CFPB] proposal utilizes a definition that is nearly identical to that of the original FDCPA,” Stamper said.

The way the CFPB proposal is written seems to have cracked the door open for state attorneys general to sue banks, the ABA said in its comment letter. And AGs from 28 states, including California, New York and Illinois, wrote a joint comment letter that suggests the CFPB has the legal authority to target banks.

The group of 28 AGs “urge the CFPB to promulgate a rule that applies equally to the activities of first-party creditors and third-party debt collectors,” their letter said. It is necessary to ensure that banks and debt collectors “are operating on an equal playing field.”

Besides AG suits, the ABA warned that the proposal “invites plaintiffs’ attorneys to bring lawsuits” against banks, too.

The CFPB’s proposal,

The CFPB’s proposal would limit a debt collector to seven calls per week to a borrower, and it adds further restrictions on when calls are made. Collectors can contact consumers an unlimited number of times through email or text messages as long as certain conditions are met.

The CFPB proposal was issued in May, followed by a public comment period that ended in September. Meanwhile, a federal appellate court’s ruling in August

The CFPB did not respond to a request for comment for this story, though officials there have said previously that the proposal is intended only to govern third-party debt collectors.

However, several trade groups for banks and credit unions have alerted the CFPB to language in the proposal that suggests it would apply to more than whom they consider to be third parties.

Public comment letters were submitted by the ABA, the Independent Community Bankers of America, Consumer Bankers Association, the Credit Union National Association, state banking associations, individual banks and others.

The proposal appears to say that if a bank violates certain provisions, such as the limit on the number of times a consumer can be called, it would be a UDAAP violation. That wording bothers bankers because banks have to comply with UDAAP standards, which are enforceable by state attorneys general as well as the CFPB.

Such a rule would fundamentally change the business model of community banks, said Isaac Schmeling, servicing manager at the $894 million-asset CorTrust Bank in Mitchell, S.D. Small banks communicate with clients frequently, he said, and limiting that would damage the relationships.

“Borrowers come to us because we have built a relationship with them,” Schmeling said in an interview. “If we talked to them yesterday but can’t talk to them now for another seven days, you’ve taken away the relationship.”

Still, some lawyers who advise banks on debt-collection matters played down the concerns, saying that it is clear that the federal debt-collection law applies only to third parties, and not to banks. If the CFPB made a mistake in including banks, there is time to correct it, said Myles Levelle, an attorney with Drew Eckl & Farnham in Atlanta.

“There’s no reason to sound an alarm at this point,” said Levelle, who represents banks in debt-collection cases.

But industry groups are nevertheless raising red flags. Banks that do mortgage servicing, for instance, are worried that they would be subject to UDAAP-related enforcement. The Mortgage Bankers Association noted that servicers already have to comply with industry-specific regulations such as the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act and the Truth in Lending Act.

“Mortgage servicing is a unique form of debt collection, governed by a comprehensive regulatory regime under the CFPB’s Mortgage Servicing Rules” and should not be subject to fair debt-collection laws, wrote Pete Mills, senior vice president of residential policy at the MBA.

Jason Lane, a senior vice president at the $20 billion-asset MidFirst Bank in Oklahoma City, said the CFPB failed to include the exemption from the federal debt-collection law accorded to mortgage debt that has been discharged through a bankruptcy court.

Without that exemption, families are at risk of being thrown out of their home through a foreclosure, Lane wrote in a comment letter.

“Unlike most debts that are part of the bankruptcy process, a creditor that holds a mortgage lien on the home of a consumer that received a bankruptcy discharge may continue to seek monthly payments instead of pursuing foreclosure,” Lane said.

The CFPB proposal could lead to significantly higher compliance costs for banks due to the need to upgrade software systems no matter how the final rule is worded, other industry observers said.

Many banks lack adequate technology to track the number of times they have called consumers and the date and time of those calls, a key part of the CFPB proposal, said Stefanie Jackman, an attorney at Ballard Spahr in Atlanta who advises banks on debt-collection laws.

“Many banks are going to need to make significant investments in technology to track and maintain all of this information,” she said.

Even if banks are excluded on debts they collect themselves, third parties will likely make more requests for additional documentation from banks, Jackman said. Many banks will not be able to handle that increased volume, she said.