A special committee formed by the Federal Reserve to study potential Libor replacements has focused almost exclusively on how it will affect the derivatives market, with virtually no consideration of the loan market.

“Loans have been the ignored stepchild in the process so far,” said David Duffee, a banking attorney at Mayer Brown, referring to the study conducted by the

The committee’s chair, Sandra O’Connor of JPMorgan Chase, said that is by design, per the specific instructions of the Fed and the

“It’s important to note that, when you’re talking about the derivatives market, most reference the Libor rate,” O’Connor, who is JPMorgan's chief regulatory affairs officer, said in an interview. “Yes, there are loans tied to Libor. But derivatives’ referencing of Libor is enormous.”

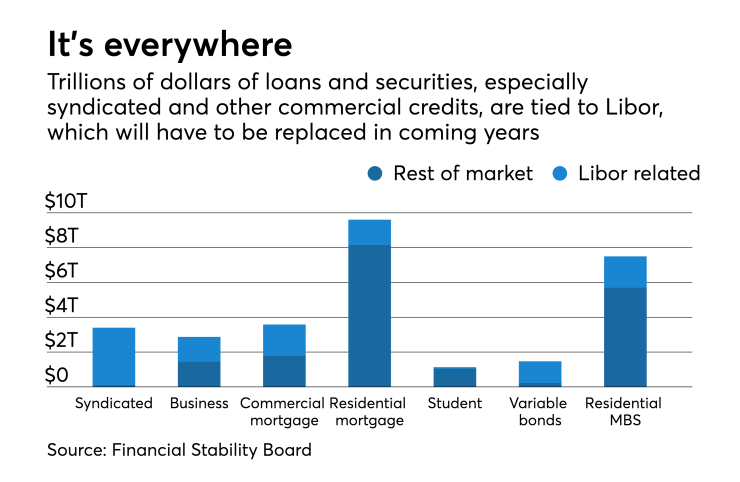

Still, the lending market’s exposure to Libor is more than chump change. The London interbank offered rate is pegged to about $350 trillion of derivatives, loans and securities. On the loan side, Libor touches everything from residential mortgages to commercial-and-industrial loans to student loans.

Libor was doomed after some of the world’s largest banks were discovered in the early part of the decade to have been manipulating it. Since then, Libor has fallen out of favor and is no longer considered a reliable gauge of market values.

The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority effectively hammered the final nail in Libor’s coffin on July 27, when it said that it will

Over the past three years, the committee that O’Connor leads has been evaluating alternatives. In June, the group announced that it had selected a broad

Unfortunately for the thousands of U.S. banks that have made loans tied to Libor, the ARRC’s recommendations have said very little about loans, said Duffee, who represents banks and borrowers in lending transactions. In

It is possible that the broad Treasury repo rate could be used as Libor’s replacement in loans, O’Connor said.

“The rate that this group selected can be used as a benchmark for anything that references Libor,” she said.

The committee’s final report will provide some details on the pace and timing of the transition. But it likely will not include a prescriptive program on how banks are to replace Libor, she said.

Banks will be given guidance on transition plans, but “specifics will be left to individual firms,” O’Connor said. “They will have to conduct their normal due diligence, just as they would when they launch new products.”

“You will need to negotiate an agreement, loan by loan, with each borrower, and it’s going to be a heavy load,” one expert says.

Absent clear guidance, banks can still get busy preparing for Libor’s replacement. The first task should be a thorough review of the documents for all outstanding loans that mature after 2021, said Cheryl Aaron, a banking attorney at Michael Best & Friedrich.

“Banks will need to renew their loans to make them explicitly rely on a different rate,” Aaron said.

That process typically will involve a bank directing its outside legal counsel to review the language in loan documents, said Alec Fraser, also a banking attorney at Michael Best. Many loan documents will already contain language that provides the lender with flexibility to use a replacement rate.

“But a bank won’t know that until they go back and look at each of their variable-rate loans,” Fraser said.

Smaller banks are more likely to have loan contracts that lack the necessary language, he said.

“We are telling our clients that they should be looking at those loan documents sooner rather than later,” Fraser said.

The process could be costly, not just because of the legal review but also any associated financial and accounting reviews, said Pri de Silva, an analyst at CreditSights. Some borrowers may balk at simply swapping out Libor with a new rate, because there will not be an exact match in value, he said.

“You will need to negotiate an agreement, loan by loan, with each borrower, and it’s going to be a heavy load,” de Silva said.

The ARRC’s preferred replacement, the broad Treasury repo rate, is likely to trade at a price below Libor. It is not going to make lenders happy to replace Libor with a lower base rate, Michael Anderson and Maggie Wang, analysts at Citi Research, wrote in an Aug. 4 report. Other adjustments will need to be proposed by the committee, they said.

The task could be monumental for banks that rely heavily on variable-rate loans. At the $72 billion-asset Comerica in Dallas. about 90% of its loans have floating rates, and the majority of those are tied to Libor, Comerica President Curtis Farmer said at the June 14 Morgan Stanley Financials Conference.

Adjustable-rate mortgages may also be a source of trouble. Libor is used as the benchmark index for about 65% of the $1.33 trillion adjustable-rate mortgage market, according to Black Knight Financial Services. Lenders and mortgage services

Other administrative tasks associated with Libor’s replacement could be much easier to complete. Banks will need to update their compliance software, but that adjustment should not be costly or difficult, said Tom Caragher, senior product manager for risk products at Fiserv.

“If you are looking at interest rate risk software, it will be pretty straightforward,” Caragher said.

Most banks probably should not worry too much about Libor’s replacement, even if regulators have not yet issued much in the way of advice, said Chris Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners. Marinac estimates that banks’ costs associated with the of Libor probably will not rise to a material event and banks probably will not need to adjust earnings estimates.

“As this should occur in an orderly fashion, it should be not be disruptive,” Marinac said. “It is probably still going to be a pain in the neck, but then again so was Tarp and the Durbin amendment, and the banking industry survived intact.”