Warnings from current and former regulators about the risks leveraged loans pose to banks have largely gone unheeded, but that could change once Democrats take control of the House of Representatives in January.

While House Democrats won’t be in position to enact legislation or force regulators to step up enforcement, they could use their newfound power to spotlight issues that Republicans in Congress have mostly ignored, including the exploding levels of corporate debt, investment analysts and attorneys say.

"If the Democrats do win the House and/or the Senate,” John Sherman, portfolio manager at DDJ Capital Management, told Bloomberg before last week’s election, “I would expect them to cause gridlock in Washington and generate more noise around enforcing some of the regulation that was enacted during the Obama administration, specifically the leveraged lending guidance.”

Leveraged loans are issued to companies that don’t have investment-grade ratings, either because they already carry high debt loads or they have poor credit histories.

According to various estimates, volume has risen from about

As demand for leveraged loans has surged, former regulators, such as ex-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, and current ones, including Todd Vermilyea, a senior associate director Fed’s regulatory division, have raised concerns about weakening underwriting standards.

“There may be a material loosening of terms and weaknesses in risk management” in the leveraged loan market, Vermilyea

Thus far, banks have largely ignored warnings as the yields in leveraged loans have been too good to pass up and demand in other loan categories has been tepid, industry observers said. They also seem to be getting mixed signals from regulators, with some sounding the alarm and others, particularly Comptroller of the Currency Joseph Otting, saying that banks have large enough capital cushions to take measured risks.

Otting last month said that when it comes to leveraged lending, banks “really kind of stayed on the rails,” mostly remaining within “relatively healthy” levels of coverage. The comments were seen as further evidence that

“Otting was barely in the door [at the OCC] and he says you shouldn’t worry so much about leveraged loans because it’s going to slow down the economy,” said Mayra Rodriguez Valladares, a managing principal at MRV Associates. “The minute any regulator tells banks that they really shouldn’t be bound by the guidance, any bank is going to go forward.”

Bankers like leveraged loans because they offer higher yields than other commercial loans and their floating rates reset at higher rates more quickly than other loans, Valladares said.

Moreover, demand from other loan categories has been too weak to justify avoiding a red-hot sector, said Julie Solar, senior director of financial institutions at Fitch Ratings.

“This is an asset class where some banks have a historic competence,” Solar said. “They’ll extend credit here even though they have higher risk exposures. There’s a broader search for yield that’s probably dominating the decision-making” by bank executives, she said.

Big banks with investment banking operations are the largest players in leveraged lending, said Eric Rosenthal, senior director in the leveraged finance group at Fitch Ratings.

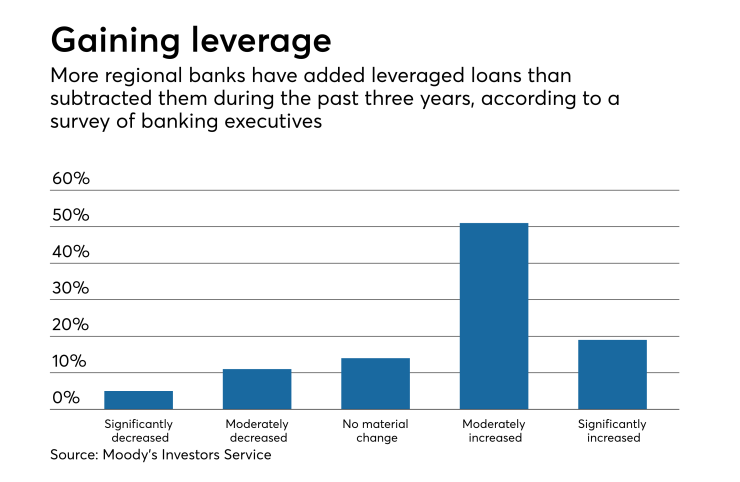

Some regionals originate leveraged loans, but not enough to be financially material. In a recent survey of 38 regional banks, including BB&T, Comerica, M&T Bank, KeyCorp and SunTrust Banks, Moody’s Investors Service found that the institutions have “relatively modest,” though growing, exposure to leveraged loans. Median outstanding leveraged loans made up about 2% of total loans at the surveyed banks.

Still, Megan Fox, an analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, said that investors are becoming concerned that banks are lowering their lending standards, such as weakening loan covenants, in order to win deals. With fewer protections in place, banks could wind up problem loans on their books, she added.

“We know that there’s evidence of weak underwriting standards industrywide, which will result in lower recoveries if those loans don’t perform when the market turns,” Fox said.

Even some bankers are wary of leveraged lending. In an Oct. 12 conference call with analysts, Bill Demchak, the chairman and CEO of PNC Financial Services Group in Pittsburgh, said that he believes the leveraged loan market is becoming “overheated.”

“As rates rise, it’s going to put real pressure on those credits that were originated in lower-rate environments,” Demchak said.

Demchak’s view is the appropriate one for any banker to take, said Hu Benton, vice president of banking policy at the American Bankers Association. Bankers must make decisions based on their institutions’ risk profiles.

“One of the things that bankers have to keep in mind is that they are in a very competitive market and they have to make decisions about what they’re comfortable with,” Benton said. “Some loans may not turn out to be as creditworthy as they anticipated. You price that risk into it.”

Isaac Boltansky, an analyst at Compass Point Research & Trading, said in a research note Monday that he would not be surprised to see regulators picking up on the warnings.

In a follow-up interview, Boltansky wouldn’t speculate on whether Democrats would pressure regulators to develop guidance on leveraged lending. But, he said, "Democrats will have the power to hold hearings, issue subpoenas and highlight issues in the public forum.”

Others suggested that Democrats could push regulators to revive Obama-era enforcement guidance, such as limiting the amount of debt loaded onto takeover targets, or press for more scrutiny of loan covenants.

Maxine Waters, a California Democrat, will chair the House Financial Services Committee. She has not yet identified leveraged lending as a specific concern, though she said last week that she would not hesitate to ask banking regulators or CEOs

“I do think it’s legitimate for the CEOs to come in and testify about what’s going on in their banks,” Waters told Reuters.

Banks are better capitalized now than they were a decade ago, but it’s questionable if they have enough capital to withstand a market meltdown, Valladares said.

“Better capitalized doesn’t mean well capitalized,” Valladares said. Most banks don’t have enough capital to serve as an adequate capital cushion if billions of dollars of leveraged loans go bad and the losses pile up, she said.

Deborah Staudinger, a banking attorney at Hogan Lovells, disagreed, arguing that banks have plenty of capital to serve as a backstop for potential deterioration in leveraged loan quality.

“As opposed to the pre-financial-crisis era, which most folks are comparing this to, banks are so much healthier and have so much capital,” Staudinger said. “Their overall risk picture is not deteriorating.”

Staudinger added that if banks don’t loosen their loan terms somewhat, they will likely lose the business to nonbank lenders such as insurance companies and pension funds that have poured into the market.

“That’s the competitive reality at this point,” Staudinger said. “If banks are going to stay competitive, they’ve got to take these risks.”