Something doesn’t add up.

Consumer credit has held up remarkably well during the pandemic, and household debt has shrunk. Even among consumers who have lost jobs or sustained other economic harm during the recession,

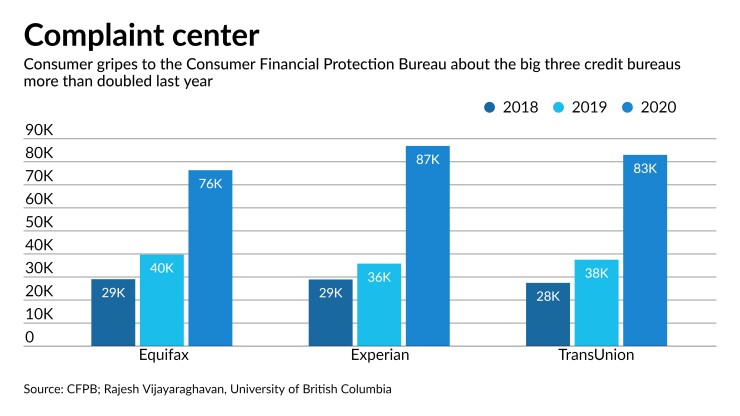

Yet the number of complaints to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau about credit reporting issues soared last year. Equifax, Experian and TransUnion were directly named in 246,000 direct complaints last year, more than double in 2019. If one includes more general grievances about credit reporting, the number rises to 283,000 — which was 58% of all CFPB complaints, up from 44% the previous year.

The spike is a mystery especially given that the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act last year required financial firms to categorize certain accounts as current for consumers affected by COVID-19. Meanwhile, debt collection ground to a halt during the pandemic for various reasons, including temporary moratoriums imposed by states.

The trade group that represents the three big credit bureaus, the Consumer Data Industry Association, is denying blame for the increase and pointing the finger at credit repair firms. These firms are filing millions of complaints to deliver on their promises of boosting consumers' credit scores, the CDIA and some credit experts claim.

“They are using the legal structure of filing disputes as a tactic to remove accurate but negative information from credit reports,” said Francis Creighton, the CDIA's president and CEO. "Banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and other regulators have not seen a decline in credit quality or any issues suggesting the credit reporting system is a problem. The problem here is credit repair."

Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, lenders must investigate every dispute within 30 days or a negative item gets dropped from a credit report. Financial firms also must respond to complaints made to the CFPB within 15 days.

Banks, credit card companies, auto lenders and debt collectors that furnish information to the credit bureaus are overwhelmed by disputes to the industry’s automated system, called e-Oscar, and by complaints to the CFPB, Creighton said. The flood of disputes often results in negative but legitimate debts being dropped from credit reports if a financial firms does not respond within the legal time frame, he said.

The CFPB acknowledged in a

The CFPB, which shares oversight of the credit bureaus with the Federal Trade Commission, has criticized them for failing to respond to many complaints during the pandemic.

In 2020 the credit bureaus "stopped providing complete and accurate responses in many of these complaints," the CFPB said, adding that the credit bureaus frequently mentioned "suspected third-party activity in their responses to these complaints, but did not detail steps taken to authenticate consumers or respond to the subject."

A lawyer representing the largest credit repair firm denied the industry’s allegations, saying consumers filed more complaints with the CFPB because of financial stress stemming from the coronavirus pandemic.

“With respect to the complaint numbers, if you plot the CFPB numbers by month, you will see a striking similarity to COVID,” said Eric Kamerath, an attorney who represents Lexington Law, the largest credit repair firm, and Progrexion Marketing, an advertising firm that owns the second-largest firm, CreditRepair.com. “People had more interest in their credit reports and more opportunity to try and deal with questions on their own.”

He said neither Lexington Law nor CreditRepair.com submit CFPB complaints on behalf of consumers. Separately, the CFPB

Credit repair firms have grown into a sophisticated industry over the past 20 years, in part because the credit bureaus have failed to adequately investigate consumer complaints, some advocates said.

"We are not big fans of credit repair," said Chi Chi Wu, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, who has sparred with both credit repair firms and credit bureaus for 20 years. "But the position that nearly 300,000 consumers are lying to the CFPB is not true."

"You can see how arrogant the credit bureaus are in dealing with their regulator, saying they are not going to treat these complaints seriously," she said. "If the credit bureaus did their job and properly investigated disputes and didn't always take the side of the creditors, there wouldn’t be this huge demand for credit repair firms."

Still, credit experts point to the doubling of complaints about credit bureaus from 2019 to 2020, and a fourfold increase since 2017, as indicators that the system for resolving inaccuracies on credit reports is not working for consumers.

“It’s massively broken,” said Michael Turner, president and CEO of the Policy and Economic Research Council, a nonprofit research firm focused on credit information sharing. “Consumers hire credit repair firms to improve their credit scores, and they work by gaming the system. They flood the system by disputing everything on a credit report that is derogatory.”

Credit repair firms are known to dispute numerous individual data elements in a credit account, Turner said. He cited one example in which 70 data elements on one person's credit report were disputed for 20 different accounts — also know as tradelines — in collections. Such disputes are wreaking havoc with a system designed to correct errors and help victims of identity theft, he said.

Another tactic used by repair firms is so-called credit washing, in which repair firms or consumers claim the borrower's identity was stolen and dispute a legitimate tradeline, typically ones that are 90 days past due and in collections. Some are able to eliminate the red flags entirely and gain access to additional credit through a different lender, said Jason Kratovil, a principal at Sivon, Natter & Wechsler and executive director of the Consumer First Coalition, an advocacy group aimed at combating identity fraud.

One midsize financial institution reported more than 1,000 instances of credit washing a month, he said.

"If you are persistent enough, you can even get a bad tradeline completely removed from your credit report and that is what some credit repair shops promise — not a temporary Band-Aid but a permanent fix," Kratovil said. “This scam definitely adds to lenders’ fraud losses and drains resources to respond to every one of these credit-washing attempts. Our goal in stopping this abuse is to ensure real ID theft victims are able to be prioritized.”

Complaints about inaccuracies on credit reports reached a fever pitch in 2013 after the FTC released a

Around the same time, the three credit bureaus were being investigatied by 31 state attorneys general and ultimately agreed to a settlement in 2015.

Under the National Consumer Assistance Plan, the bureaus agreed to remove most civil court judgments and tax liens from credit reports that did not include identyifying information. However, bankruptcy judgments remain. The settlement also imposed a 180-day “waiting period” on medical debt from showing up on credits reports while medical debts paid by insurance companies were removed altogether.

The settlement also required that debt collectors provide the original creditor’s name and information about a debt before it could be added to a credit report.

Yet the credit bureaus continue to dispute the FTC study, claiming there is a big difference between minor errors on credit reports — such as a person's address being listed incorrectly — and material errors that affect a consumer’s credit score and ability to obtain credit.

"If you live on Wisteria Lane, but some credit card company recorded you as Wisteria Street, that’s an error, but not a material one," said Creighton.

In the

Because most court records and tax liens have since been removed from credit reports, Turner at PERC suggests the industry’s material error rate today is close to 1%.

“If you had a database with quality control measures that is 99% accurate, you’d be happy with that,” he said.

Despite the changes, consumers still complain about having a hard time getting legitimate errors removed that leads them to hire credit repair firms, advocates said.

"We have seen cases where the consumer disputes and disputes and the error doesn't get fixed until they hire a lawyer," said Wu at the National Consumer Law Center. "The industry is notorious for spinning facts."

Some credit repair firms said they file disputes because consumers often do not recognize the names of debt collectors, even though the settlement requires that original creditors be listed on credit reports.

“If the consumer doesn’t know the basis for a tradeline being on the credit report, the consumer should be entitled to ask and be able to look at their information and records to determine if it lines up,” said Kamerath. “I hear criticism that furnishers get stacks of paper that comes in the mail every day, but it’s a fraction of what [debt collectors] send out.”

Perhaps the bigger tragedy, credit experts said, is that true victims of identity theft are getting lost in the scrum.

Consumers who have had their financial information stolen can file a claim with the FTC on identitytheft.gov. But in 2017, the FTC removed a requirement that consumers provide a police report to verify they were a victim of identity theft, creating an opening for credit repair firms, some experts said.

"Taking away that police report requirement pretty well opened the floodgates for credit repair organizations," said Kratovil. "Now actual victims of identity theft are lost in the morass."

The overall cost of credit repair firms disputing claims is hard to quantify.

There are more than 11,000 credit furnishers and each has to pay 30 cents per transaction to use e-Oscar to resolve disputes. Much of the correspondence comes in the mail, so credit furnishers, many of them debt collectors, have to hire employees, supervisors and lawyers to process and investigate millions of disputes a year, as required by the FCRA.

"We all are bearing the cost of credit repair clinics," Turner said. "The more accurate negative information we remove, the more errors are made and the cost of credit goes up for everybody."

A director at e-Oscar declined to comment or disclose how many disputes are filed with the online data exchange every year. The three credit bureaus referred inquiries to their trade group.

Longtime credit expert John Ulzheimer, president of Ulzheimer Group in Atlanta, said repair firms flood the system with disputes that primarily challenge negative but accurate information.

"Credit repair is often positioned as assisting consumers with getting credit report errors corrected or removed, but they rely on the consumer saying what is an error versus what is legitimate, which leads to disputes being filed on negative, but accurate, information," Ulzheimer said.

Last year, Lexington Law created a new trade group, the American Association of Consumer Credit Professionals, that a spokeswoman said is advocating on behalf of minorities, seniors and the unemployed who have been hit hard by the pandemic.

“A consumer comes to us and says there’s all this stuff on [their credit report] that is not [theirs], it’s wrong or fraudulent and they are looking for other resources for how to survive,” said Liz Shrum, a senior adviser and spokesperson for the group, which has two other members, Progrexion and CreditRepair.com.

Shrum initially claimed the group's three affiliated members only dispute issues on credit reports related to identity theft or errors that need to be fixed on credit reports. She then expanded on the firms' practices.

“If there’s been a mistake or someone stole their identity, we send letters to ask the debt collectors to investigate that on behalf of consumers,” Shrum said, adding: “We ask for there to be investigations of inaccurate, unfair or unsubstantiated items on credit reports.”