Student loans are supposed to be a bulletproof asset class for securitization. The debt cannot be discharged in bankruptcy; moreover, the government guarantees most loans. Investors can be sure they will be repaid.

But as recent events have shown, they can't be sure exactly when they'll be repaid. And that uncertainty has roiled the normally staid market for bonds backed by Federal Family Education Loans, prompting downgrade threats from the rating agencies and a steep sell-off over the summer.

At issue is the impact of Income Based Repayment, a generous government plan for borrowers struggling under the weight of student loans. The program, which Washington has aggressively promoted in recent years, slows down the rate of repayment, sometimes to as long as 25 years from the standard 10. This creates a problem for anyone who invested in a securitization, since bonds issued from these deals may not pay off at their final maturity.

“This is sort of a paradigm shift. … A lot of people viewed this as money good paper,” said Debash Chatterjee, a managing director at Moody’s. “It still is money good, but there’s a lot of uncertainty as to when investors get repaid.”

Whether or not you consider failure to pay off at maturity to be a "default," extension risk is never a good thing. And it's particularly troubling given the outlook for interest rates. Although the broader market turmoil of recent weeks could delay a Fed rate hike, rates are expected to rise eventually, but the student-loan bondholders' principal may be unavailable to reinvest for a longer period of time.

The issue has surfaced amid mounting concerns that the more than $1 trillion in outstanding student debt could contribute to the next financial crisis. The situation also echoes the years after the mortgage crisis, when government efforts to help struggling borrowers clashed with investors' interests. Unlike the mortgage market, however, the student loan sector wants for loan-level disclosures, making it hard for investors to know their exposure to extension risk.

Late Bloomer

Ironically, IBR, the program whose recent success with borrower uptake started all the troubles, was initially a dud.

Enacted as part of the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007, it had a July 1, 2009, start date. But in the first year or two, the take up was much, much lower than expected, despite the favorable terms. For those who qualify, monthly bills are capped at 15% of their discretionary income, and after 25 years of payments any remaining debt is forgiven.

According to Mark Kantrowitz, one of the plan's designers, during the initial implementation, borrowers were unable to simply select IBR on the Department of Education’s website; the pull-down menu of payment plans did not list it as an option. Instead, borrowers had to fill out a paper form and mail it to the government agency.

“It was a bureaucratic nightmare,” Kantrowitz said.

Since then, there has been a lot of pressure to increase the number of borrowers in the program amid concerns that the burden of student loans is forcing borrowers to postpone marriage, childrearing and home purchases. Under President Obama, the department has both made it easier to enroll and stepped up marketing.

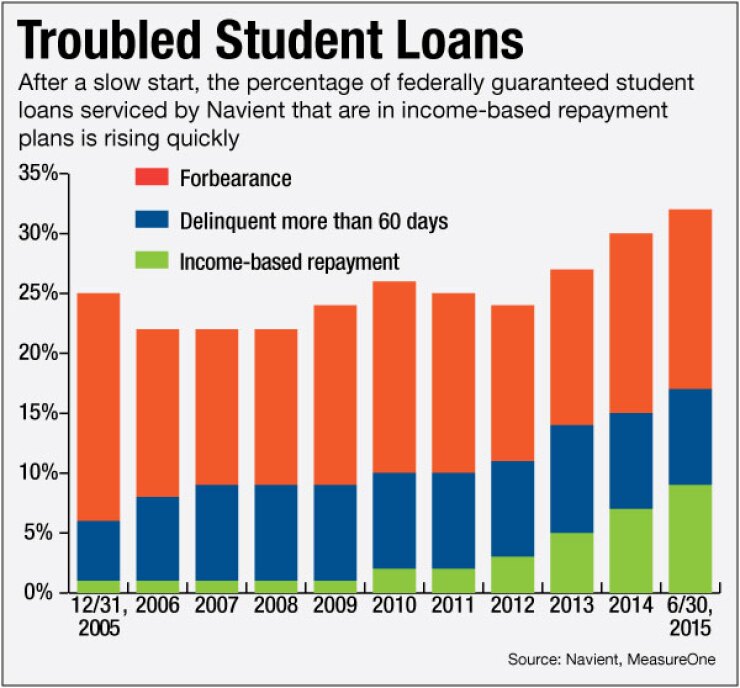

The impact has been marked. While the federal government doesn’t track the repayment status of FFELP loans, as of the end of June 3.9 million borrowers with Direct Loans (those made by the federal government since 2010) were enrolled in some kind of income-based repayment plan, according to the department. That’s a 56% increase from June 2014.

“So now we have the opposite problem,” Kantrowitz said. “People who are capable of making monthly payments on one of the other plans are in IBR because it’s been presented as the default choice. The government was so aggressive in getting people into it that it got people who maybe didn’t need it.”

Kantrowitz, the senior vice president and publisher of Edvisors.com, said that IBR “was intended to be a safety net, not the standard repayment plan for most borrowers.”

Spooked Over Hidden Risks

The delayed interest in IBR isn’t the only reason that investors, as well as ratings agencies, were slow to catch on to the impact of slower repayments on student-loan backed securities. The companies that service these deals simply do not disclose much information about individual loans, including their payment status.

Now the word is out.

Over the summer, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings put nearly $40 billion of FFELP bonds under review for a possible downgrade, citing the likelihood that they would not pay off at maturity. In some cases, these bonds, which are currently rated triple-A because the federal government guarantees at least 97% of the principal and interest, could be cut by Moody’s to below investment grade.

This has sparkedthe selloff. Spreads on shorter-dated FFELP bonds, those with terms of between 1.3 years and 1.5 years, widened to 94 basis points in August from 41 basis points in July, according to research published last month by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Spreads on intermediate-dated tranches, those with terms of four to five years, rose to 153 basis points from 73 basis points. And spreads for tranches with terms of 5.8 years to 7 years widened to 163 basis points from 91 basis points.

Analysts at BAML said the moves reflect both concerns about cash flow interruptions and rating downgrades as well as broader market concerns. "Both of these factors likely mean spreads will move to wider levels,” the report states.

Moody’s, which has now obtained loan-level data on borrower-repayment status from Navient and from Nelnet, the two biggest servicers, reckons that as much as 15% of borrowers in some securitizations of nonconsolidated FFEL are in income-based repayment. And more than 50% borrowers in IBR are making no paymentsbecause they don’t meet the minimum income threshold, while 25% pay only interest.

And these figures don’t take into account borrowers who are in other kinds of forbearance programs or are simply behind on payments.

Chatterjee said that this was even higher than the ratings agency had expected. We were “a little surprised,” he said. By contrast, many investors it spoke with on a July 15 conference call were “shocked.”

Dicey Outlook

If current trends continue, Moody’s believes that many FFELP bonds could default, beginning with those maturing in 2018 and 2019. Chatterjee emphasized that actual losses would be negligible, since the federal government will ultimately make good on any loans that default. But it’s unclear when investors would be repaid.

Moody’s plans to change its ratings criteria to incorporate the assumption that a certain number of borrowers will remain in deferment or in an income-based-repayment plan for some time, and adjust repayment and default assumptions accordingly. It has published guidance on the proposed criteria changes and is accepting comments until Oct. 30.

Chatterjee also sees political risk for the asset class. “You could see future modifications to policies that might take a different stance on repayment plans, which, depending on the direction, could be either positive or negative for the [asset-backed securities],” he said.

Fitch also considers bonds that fail to pay off by their final legal maturity to be in default. It has placed $8 billion of FFELP ABS under review for a potential downgrade and is also reviewing its ratings criteria to address the slower rate of repayment.

Market Reactions

The ratings reviews and subsequent selloff of FFELP bonds have spurred servicers into action. In addition to providing loan-level data on repayment status to Moody’s, Navient, the biggest student loan servicer, has also distributed this data more widely, making it available to Intex, a company that provides cash-flow analytics for various kinds of structured finance, and MeasureOne, a company that collects, analyzes, and distributes student loan data.

Navient has also amended 17 securitization trusts since 2014 to allow it to buy back 10% of the initial assets. As of June 30 of this year, it had exercised loan purchase rights for $428 million. Additionally, through the first six months of this year, Navient called $212 million in bonds. On Aug. 6, it announced plans to call three additional trusts and for an additional $216 million in bonds.

The sponsor has the capacity to hold about $11.5 billion through various conduit facilities and plans to eventually resecuritize the loans over time.

Access Group a not-for-profit student loan administrator (and former lender/servicer), has announced that it is also calling a tranche of one three of its deals under review from Moody’s.

Moody’s believes that, while loan repurchases can help mitigate the impact of slower repayment on bonds backed student loans, the rating of a deal’s sponsor will determine the benefit that can be given to the securitization. “A triple-A security cannot be supported by an optional purchase promise from a below-investment-grade sponsor,” Chatterjee said.

Likewise, Fitch will consider the ability of the issuer to make such purchases to determine if the risk has been sufficiently reduced, according to a report it published Aug. 18.

Another option that Navienthas under consideration, according to Joe Fisher, vice president of investor relations, is repackaging certain FFELP ABS tranches into new securities with extended maturity dates. In its simplest form, an existing tranche with heightened maturity risk would be placed in a trust and a new security with a longer maturity date would be issued in its place.

This might not pass muster with Moody’s, however. Chatterjee said that extending the maturity of FFELP bonds, when accomplished by issuing new, longer-dated securities in exchange for existing securities, could be considered a distressed exchange, which is another event of default.

In its August report, Fitch said that a new security issued via repackaging could, in theory, obtain an ‘AAA’ rating, but the original rating of the underlying security will remain outstanding and could face downgrades.

Navient believes that a fourth option -- extending the legal final maturity dates for existing bonds – would be the “cleanest and the best” solution, Fisher said. The challenge, however, is that it requires rating agency and 100%, in some cases, bondholder approval on what the new legal final maturity date would be to maintain a triple-A rating, he said.

Fitch’s report states that a “missed original maturity date would not be considered an event of default if all bondholders agree to the extension.”

For new FFELP securitizations, Moody’s has endorsed a specific fix: a so-called turbo feature. After a certain date, excess cash that would otherwise have “leaked out” to holders of the residual interest in the deal (typically the sponsor), will be used to pay down bonds.

There have been at least two deals issued that incorporate this feature; Moody’s has assigned a ‘AAA’ rating to the senior tranche of each deal. The first, from Navient, was completed in April. In addition to benefiting from a turbo feature, the senior notes have a longer final maturity than those of Navient’s previous deal, completed in January.

The second deal, from Access Group, came to market in July, as spreads on FFEL ABS were gapping out in response to Moody’s review of its ratings criteria, increased funding costs for the sponsor. Yet Access Group still went through with the transaction, which was a refinancing of a deal originated in 2008, during the financial crisis.

Wake-Up Call

While other issuers are looking at similar ways to mitigate the impact of slower repayment on student loan-backed securities, it remains to be seen whether they will follow Navient’s lead and release loan-level data on repayment status.

MeasureOne has analyzed the loan-level data that Navient has disclosed and is sharing its conclusions with investors who respond to a survey on their data needs.

“This situation with IBR is a wake-up call for investors,” said Dan Feshbach, the company’s founder and chief executive. “It’s the classic risk you don’t know and is exacerbated by not having access to granular data.”

Before MeasureOne, Feshbach founded LoanPerformance, a mortgage analytics company that is now part of First American Corp. He said that the student loan industry “is not even close to where the mortgage industry was in data disclosure in 1992, when we started the LoanPerformance jumbo mortgage securities data base, or in 1997/1998 when we started our subprime and alt-a databases.”

Why haven’t student loan investors demanded more disclosure before? Feshbach said that different investors have different reasons. One group is comfortable with the government guarantee, and has until now not seen the risk; another group has developed an “information advantage” and is OK with the spreads that exist on these securities because there is not a lot of information.