The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency designed its fintech special-purpose national bank charter proposal with the best of intentions: to foster

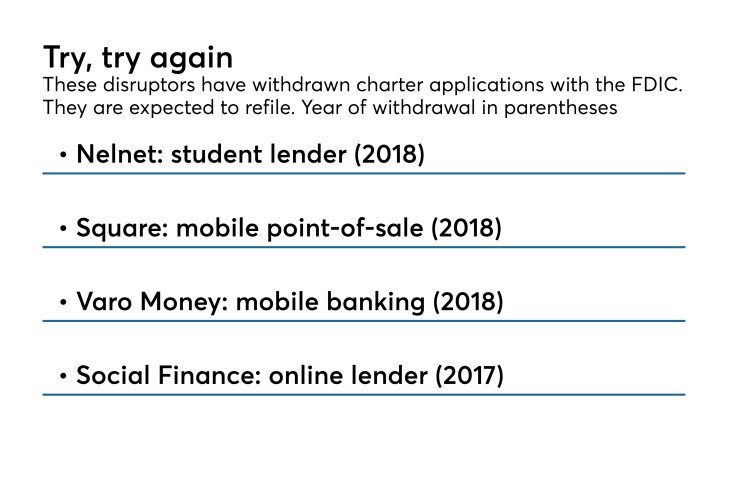

The OCC’s proposal was also a reaction to the almost complete failure of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. to grant deposit insurance to innovative banks, and to the Federal Reserve’s cramped reading of its own control regulations, which have inhibited venture capital and private equity investment in new types of technology-driven banking.

While the OCC introduced the new fintech charter with

Now that the OCC has started the ball rolling, the FDIC and the Fed can act to fix roadblocks they themselves have created. Two policy changes will help achieve this: opening insured depository banking to fintechs and simplifying bank-control rules.

In many ways, the OCC’s uninsured, non-deposit-taking national bank looked like an ideal vehicle for national fintech lenders and payments processors. It would be a national bank for all legal purposes, could export interest rates and fees nationally without concern for usury laws, and would generally be exempt from other state licensing requirements. Because an OCC fintech bank would not be considered an “insured bank,” its controlling owners wouldn’t be subject to the

The fintech charter didn’t eliminate all of the costs of being a national bank, as charter recipients would become subject to bespoke capital and liquidity regulation and community reinvestment-type obligations. But all in all, it looked like a pretty good solution.

Yet the OCC fintech charter has a big “chicken and egg” problem. It turns out that until a fintech actually gets a fintech charter there’s no way to begin to resolve the serious legal, regulatory and political issues that go to the heart of the charter’s value and utility. And the issuance of a charter — itself a multiyear process — will be only the beginning, with years of litigation and political risk and no guarantee of a positive outcome. While I’m sure at some point someone will find a reason to take the plunge and apply for a fintech charter, it will take nerves of steel and a very deep pocketbook to pursue the game to its conclusion.

The issues that bedevil the fintech charter are complex. Let’s start with the

The second problem is that direct access to the Federal Reserve payment system is not guaranteed to fintech banks. The ability to initiate transactions at low cost over the Fed’s rails — something that only traditional banks have today — is vitally important to both payments and lending-focused fintechs. The Fed has

Then there’s politics.

So, what could change this dynamic and give fintechs a real option for federalizing their operations? The solution lies where part of the problem was created: at the FDIC and the Fed.

First, the FDIC should start issuing insurance to fintech-style banks chartered by the OCC and the states. The FDIC, working with other regulators, has all the power it needs to supervise and ensure safe and sound operation of fintech banks that take deposits, have full payment system access and are subject to comprehensive, tailored regulation. Deposit taking doesn’t have to be a core part of a fintech’s business for this to work, but getting deposit insurance does. Importantly, by allowing fintechs the choice to become insured banks or remain state regulated, legitimate state concerns about regulation of nonbanks and the sanctity of the dual banking system will be fully resolved. Recent encouraging

Second, the Fed needs to amend its “control”

So, let’s give two cheers to the OCC for trying to break the logjam preventing fintech participation in the banking system. For the FDIC and the Fed, it’s time to show leadership and get the rest of the job done.