This is the seventh of 10 articles taking an updated look at our most widely read stories of the year. The first six can be found here:

As key interest rates turned negative this year in Europe, everyday financial transactions entered the realm of fun-house mirrors.

German banks charged depositors for the privilege of holding their funds; Danish consumers received interest on funds they had borrowed; Spanish homeowners saw their mortgage principal whittled down as their bank paid them instead of the reverse.

Asset-backed securities have, so far, managed to avoid this scenario, thanks to an understanding among market participants that a special purpose vehicle (SPV) cannot, by its very nature, collect a payment from noteholders.

“It is our understanding that the interest paid from the SPV to the investor cannot drop below zero, because it wouldn’t make a lot of sense for the whole system,” said Sebastian Schranz, an analyst at Moody’s Investors Service.

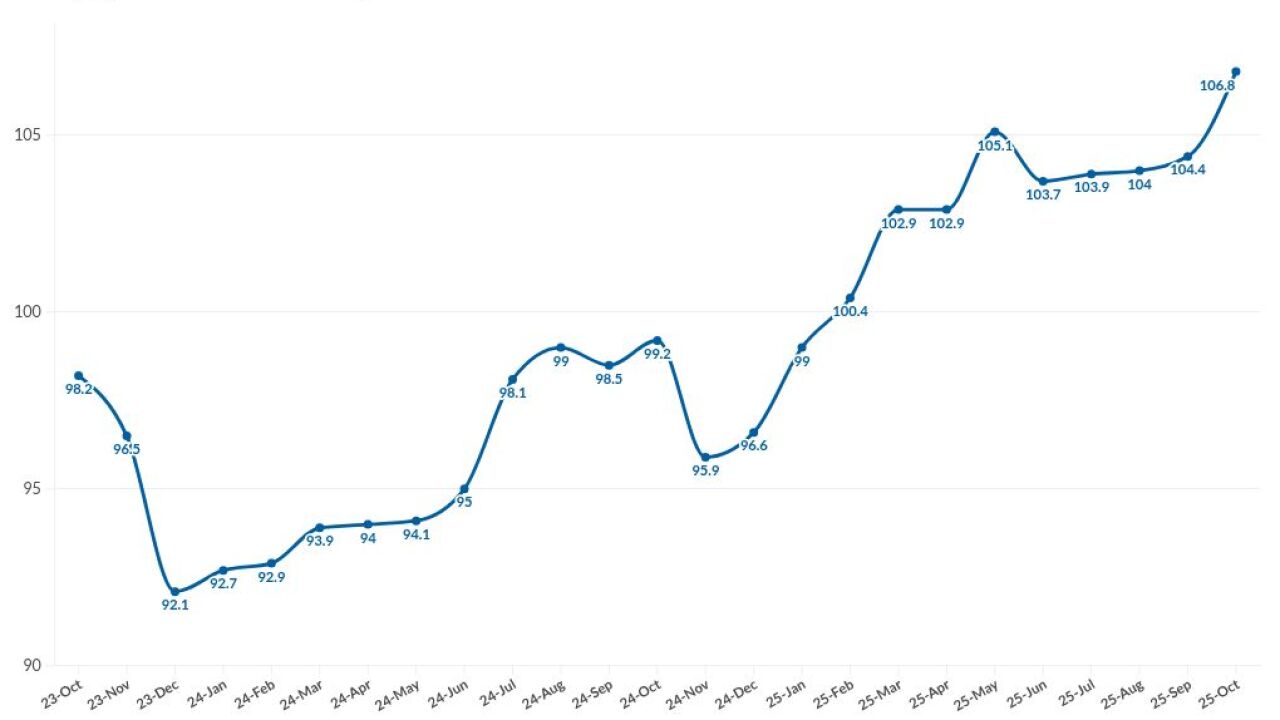

What is more, even though benchmark rates have fallen further into negative territory this year —the three-month Euribor is now at negative 0.128%, having slipped below zero in April— spreads on the senior notes issued in European securitizations remain high enough to keep the absolute yield positive.

But even if yields on asset-backeds remain in positive territory, negative interest rates are still impacting these securities in other ways. One is through the interest-rate swaps used by many European deals to hedge against basis risk. Swaps are agreements to exchange one set of cash flows for another. The assets most typically securitized in Europe pay fixed interest rates, while the bonds backed by these assets pay floating rates. This creates a potential mismatch that must be hedged; otherwise rising interest rates could eat away all of a deal’s excess spread.

So these SPVs enter into a fixed-floating swap agreement; they agree to pay a set amount each month to a counterparty, and this counterparty agrees to the pay the SPV a spread over a benchmark.

Normally, the swap leaves a securitization’s sponsor indifferent to decline in benchmark rates, since the payments from the counterparty would fall in step with interest payments due on asset-backeds. But if a benchmark interest rate falls too far into negative territory, it’s possible that the SPV will have to pay the counterparty more than just the agreed-upon amount.

Here’s why: Say an SPV issues notes paying 50 basis points over one-month Euribor. It enters a swap, agreeing to pay a counterparty 200 basis points in exchange for 50 basis points over one-month Euribor. If one-month Euribor falls to negative 150 basis points (it’s nowhere close to this, but for the sake of argument), then the SPV would have to pay 100 basis points to the counterparty, the difference between 50 basis points and negative 150 basis points. And this would be in addition to the 200 basis points.

The result? The excess spread available to bondholders would be diminished, or even exhausted.

The solution is to ensure that the floating-leg of swap can’t go negative no matter how deep into negative territory the rate has gone, which is what European securitizations have been doing this year.

Schranz it has become standard practice in securitization vehicles in Europe to floor the floating leg in the fixed-floating swap at zero. This approach — called the zero interest-rate method, is part of the swap documentation as defined by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). Under 2006 ISDA definitions, it’s not the default approach, which would allow the floating leg to breach zero. As a result, deals have been explicitly including the zero interest-rate method in the swap confirmations.