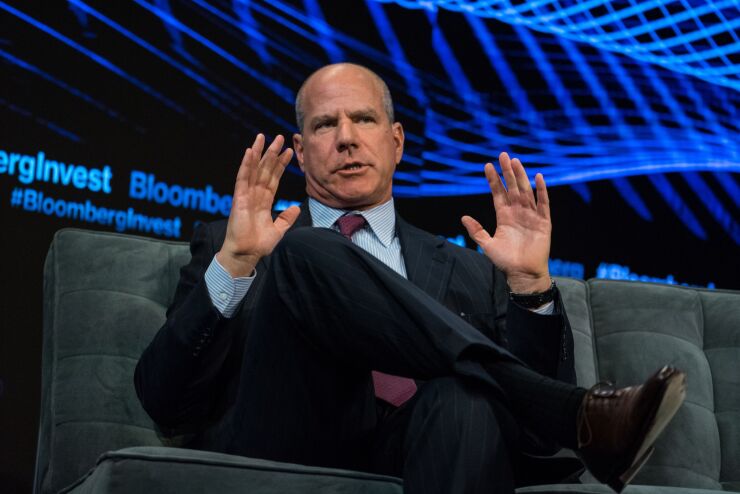

Now that TPG Capital has steered its $88 billion of investments through the first phase of the coronavirus crisis, co-Chief Executive Officer Jon Winkelried is turning his attention to other issues, like picking up the pace of dealmaking.

“How forward-leaning do we have to be in order to make sure that we capture our share of really good opportunities as we go through this,” he said in a Bloomberg “Front Row” interview. “A risk factor in my mind is: Are we not being responsive enough? Are we being too slow?”

Winkelried, 60, has a lot of other things on his mind, too. He worries about the stresses on his employees, he’s alert to the growing risks around TPG’s assets in China, and he’s outraged at the state of race relations in America, thrown into sharp relief by the police killing in Minneapolis of a defenseless George Floyd.

But it says a lot about the trajectory of the pandemic that one of the country’s biggest private-equity firms has shifted its posture from defense to offense. Just three months into the deepest economic decline since the Great Depression, it could be that now is the time to buy before the best bargains are gone.

TPG did its

“A society evolves as we go through different crises,” he said. “We’re spending a lot of time thinking about the environment that we’re living through right now and what it’s going to feel like on the other side.”

For many in private equity, the focus is on credit.

That’s not an option for TPG. The firm agreed in January to sever ties with its private-credit affiliate, Sixth Street Partners, and can’t start a competing business until 2021.

Lifestyle and entertainment experiences, fitness and travel were among the trends that flourished amid the economic stability and relative prosperity of the decade after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. TPG chased them on the way up, investing in companies such as Cirque du Soleil, Viking Cruises Ltd. and the Life Time chain of gyms. Now the firm is trying to keep those businesses afloat until demand recovers -- and betting it does.

To manage, Winkelried drew on lessons from a 27-year career at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and his experience in crises dating to the early 1980s. He said some TPG companies have had to furlough or fire workers to cut costs. And to ensure they had enough cash, a number tapped bank credit lines, received injections from TPG funds or took advantage of government aid.

He acknowledged the controversy around the use of taxpayer funds to prop up private-equity investments. TPG decided it didn’t qualify for the Small Business Administration’s forgivable loans under the Paycheck Protection Program and returned that money, he said. It did take advantage of Health and Human Services Department programs that provide advances on expected revenue from the government.

“We had a number of health-care companies that are providing vital essential services to the constituents that they serve and were impacted by the situation with Covid,” Winkelried said. “It allows them to stay in business and continue providing the services that are critical and important services.”

In addition to the $11.5 billion buyout fund it raised last year, TPG, with headquarters in San Francisco and Fort Worth, Texas, also amassed $2.7 billion specifically for health-care deals.

One major risk unrelated to the pandemic is potential fallout from the Trump administration’s fight with China, where TPG has about $2.5 billion of investments. Others among its more than 200 portfolio companies rely on Chinese supplies.

The U.S. government’s disputes with China have mostly concerned trade, technology and security. But President Donald Trump has taken steps toward cracking down on Chinese companies that violate U.S. accounting rules, throwing open the possibility that the battleground expands to include finance.

TPG is already moving to reduce its dependency on the Chinese supply chain, Winkelried said.

One of the outcomes “could be that relationships and economic activity effectively freezes between the U.S. and China,” he said. “You do have to worry about the level of investment, how much value you have as an investment organization, what you’re flowing to China. Because if it gets stranded or if it gets frozen for some reason and you can’t get your money out, then obviously it has significant implications.”

As co-CEO alongside Jim Coulter, one of Winkelried’s initiatives has been improving gender balance at TPG’s company boards. Over the past two years, the firm has added 75 female directors. Now the priority is people of color and those who identify as LGBTQ.

Like millions of Americans and much of the world, Winkelried was horrified by the killing of Floyd, an unarmed black man, by a white cop on May 25, and he’s transfixed by the anger and civil unrest that has followed. He and his wife, Abby, participated in a demonstration in Northern California, where he’s been staying during the pandemic.

Winkelried, at TPG’s weekly meeting held virtually on June 1, set the tone for the rest of the firm by devoting the entire discussion to racial injustice and diversity.

“Hostility toward people of color but also other underrepresented groups is something we’ve been living with for a long time, and it just has to change,” he said in the interview. “It’s time to do something about it. People in the streets, I encourage that. I applaud the protests.”