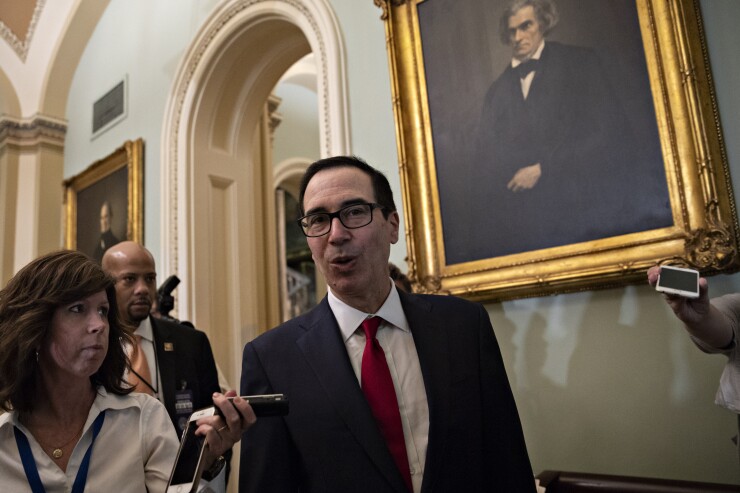

A federal watchdog is looking into former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin’s decision to roll back the U.S. Federal Reserve’s emergency lending programs at the end of 2020, an issue that has become a point of partisan tension in Congress.

The Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery is also inquiring into Texas Republican Sen. Ted Cruz’s role in persuading the central bank to expand the eligibility rules for the Main Street Lending Program to make it easier for oil and gas companies to apply for the low interest rate loans.

The probes were revealed in the watchdog’s quarterly report released Monday.

The investigations, led by Brian Miller — the special inspector general in charge of overseeing the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve’s response to the pandemic — could shed more light on Mnuchin’s decision and legal basis for winding down the programs, which Democrats say was politically motivated.

The probes mark some of the biggest moves yet for Miller, a Trump appointee, who has said he struggled to begin his oversight work since he was confirmed by the Senate in June because of technical challenges and the time needed to hire experienced staff.

Sarah Breen, a spokeswoman for SIGPR, said that Treasury responded to the inquiry about the Fed facilities on Jan. 19, the final full day of Trump’s administration. She said that any concerns abut the discontinuation of the Fed facilities was rendered moot because of the compromise lawmakers reached in the December stimulus legislation, though that position may not reflect the views of the current administration. Breen also said that they have not received a reply to the Jan. 6 letter about Cruz’s influence on the Main Street Lending Program.

Cruz’s office didn’t have an immediate response.

Stimulus debate

The future of the Fed’s emergency lending powers was a key point of debate leading up to passage of pandemic relief legislation in December. Republicans pushed to make it more difficult to revive the programs and Democrats wanted to preserve the emergency lending structures. The two parties eventually reached a compromise allowing Congress to approve similar facilities in the future after stalling the stimulus bill for days.

Mnuchin in mid-November said at year’s end he would pull unused money authorized by the Cares Act in March to back Federal Reserve emergency-lending facilities. The Treasury also unveiled plans to park those funds, along with other left-over lending authorization — some $455 billion in all — into the department’s general fund, over which Congress has authority, rather than the Exchange Stabilization Fund, over which the secretary has greater discretion.

Lawmakers including House Speaker Nancy Pelosi argued that the actions amounted to a misreading of the law and were politically motivated to hamstring the incoming Biden administration.

The probe also looks into changes made to the Main Street lending process, which Senate Democrats have said allowed indebted oil and gas companies to qualify for loans that should have gone to other companies hampered by the pandemic.

Energy companies accounted for 13% of all loans made through the Main Street program as of the end of November, according to BailoutWatch, a climate advocacy group tracking government stimulus spending.

Several Trump administration officials, including Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette and Mnuchin, worked with the Fed when the program was first being designed to allow for more mid-size companies, and therefore also energy companies, to access the facilities, Brouillette said in May.

The Fed said at the time that it didn’t make modifications to the program to specifically accommodate energy companies. By law, its emergency facilities cannot target specific sectors.

In total, SIGPR says it has five preliminary investigations underway and that it received and vetted 27 complaints during the most recent quarter. The report did not say when it plans to publish any of its findings.

“SIGPR’s aggressive preparation — while investigations and audits are by necessity and design conducted behind the scenes — will remain largely invisible to the public until charges or complaints are filed or audits are announced,” the report said. “Ferreting out financial fraud is complex and takes time.”