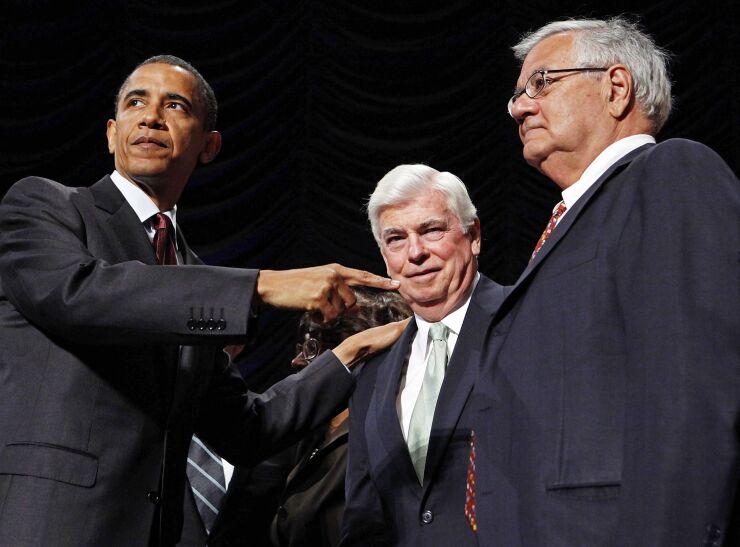

Since the moment Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, a landmark 2010 law meant to empower regulators to contain and limit the impact of the next financial crisis, there’s been debate over whether it went far enough to accomplish its goal.

We’re about to find out.

The novel coronavirus represents the first real test of Dodd-Frank, and in a way that none of its architects foresaw. And though many bankers continue to dislike and resent Dodd-Frank, they had better pray it holds up — both for the good of the economy in the short term and the future of financial regulation in the long term. Here’s why: Dodd-Frank represented a compromise between those who wanted to upend the system by breaking up big banks and restructuring the regulatory system and those who wanted less drastic changes. The result was a law that included a number of sweeping alterations, but left the structure of the system intact.

At the time the law was being written, the focus was on new financial products and institutions that could wreak havoc on the economy. Policymakers wanted to prevent the spread of new products that helped fuel a wave of foreclosures and drove housing prices down. As a result, regulators were given additional powers to spot these early and stop them if necessary. As a backstop, regulators were required to enforce tougher capital and liquidity standards to ensure banks were more resilient overall.

But risky new financial products and institutions aren’t the threat facing us now. Instead, it’s a deadly virus that spreads relatively easily through communities. Governments worldwide are taking increasingly severe measures to contain the spread, including quarantining whole geographies.

It appears likely that large portions of the U.S. are about to be significantly disrupted — potentially for months. Schools

All of this is already creating an economic impact. The markets are in turmoil. The tourism industry is under siege. Layoffs

And, unfortunately, this is just the beginning. As people stay home, many small businesses like restaurants will be severely impacted. Banks will be on the front lines, whether ensuring access to cash or offering short-term emergency loans to customers. Italian and U.K. banks are already offering mortgage forbearance. U.S. federal regulators are encouraging banks here to work with customers.

In a meeting with President Trump on Wednesday,

They have more capital, and perhaps more important, they are more liquid. What’s more, for the past decade, the biggest banks have undergone rigorous stress tests designed to probe what happens if an economy suddenly collapses. These exercises will be vital in the days and weeks ahead. They not only help banks prepare for the worst, they boost public confidence in the banking system, which is critical in any crisis.

But that strength is in large part due to Dodd-Frank, which significantly increased capital, liquidity and other requirements and codified the stress tests into law. The statute gave the Federal Reserve extra powers to address any deficiencies it uncovers. The question now is: Was it enough?

If the banking industry perseveres in the weeks and months ahead, bankers will have real, tangible proof that Dodd-Frank helped make the system safer.

If, however, we see another wave of bank failures and another bailout, public anger against banks is likely to make a resurgence. The calls for far-reaching structural reforms are likely to get louder and carry more weight. At the very least, regulation of banks will tighten.

Did Dodd-Frank do enough? Banks have a lot riding on the answer.

Rob Blackwell is the chief content officer of Promontory Interfinancial Network. He is the former editor-in-chief of American Banker. The views expressed in this article are his own and not those of Promontory Interfinancial Network.