Bankers are worried the escalating trade spat between the U.S. and China could lead to a full-blown credit crunch in America’s already debt-strapped farm country.

Agriculture lenders watched with concern last week as President Trump hiked tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods after bilateral trade talks began to sputter. The move was met with an announcement from China earlier this week of fresh tariffs on 5,000 U.S. exports, including some crops.

Farmers and their bankers have been dealing with falling prices for their harvests over the past few years. Many have been quietly putting up their farmland as collateral to borrow more funds to cover the previous year’s shortfall between their income and planting costs, according to several banking sources interviewed for this story.

While the problems have yet to eat through the vast amounts of equity farmers built up during the previous decade’s crop boom, some — especially those nearing retirement age — are being advised to sell off now, the sources said.

“The trade difficulties are icing on a very bad cake,” said John Blanchfield, an industry consultant at Agriculture Banking Advisory Services. “If this China thing blows up as it is doing right now, my worry goes from about a 6 to a 9.5.”

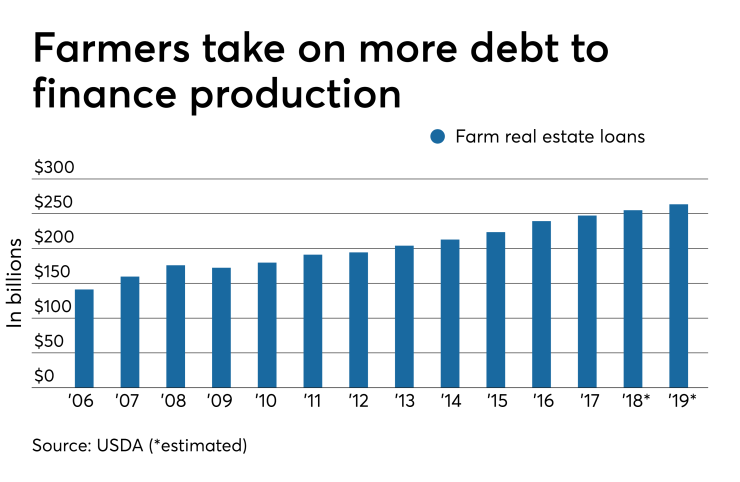

In each of the past of seven years, farmers have seen their average debt loads take a higher percentage of the equity they hold via the value of their land and equipment, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A forecast of 16.1% debt-to-equity ratio for 2019 would be up from 12.7% in 2012.

And farm real estate debt is expected to reach $263.6 billion this year, according to the USDA, which would be up from $247 billion in 2017 and $176 billion at the height of the financial crisis.

Meanwhile,

Farmers’ debt problems are still below the high-water mark of the ag industry’s collapse in the 1980s, when debt-to-equity ratios crested at 28%, past USDA data show. But if farmland real estate values underlying these loans begin to slide, the problem could get out of hand in a hurry, Blanchfield said.

“We’ve gone from a permissive credit environment to a much more restrictive environment,” Blanchfield said. “I would not be surprised in the near future to see headlines like ‘farm loan credit crunch.’ ”

Kansas Bankers Association CEO Doug Wareham grew up on a farm his family nearly lost twice even though his father was an agriculture banker. Ag bankers are not overly concerned yet, he said, but lenders and their farming clients — many of them neighbors — are being more proactive about restructuring their debt when they can.

“We would encourage the president and his agriculture trade representatives to hammer out an agreement with China so we can get back to a stable footing,” Wareham said.

Most of the damage is being felt by soybean farmers. Future prices on soybeans hit a 10-year low Monday, when they dipped below $8 per bushel. The price rebounded some in recent days when Trump announced negotiations with China would be renewed in June.

Pain among crop growers is expected to spread to ranchers, too. Heather Malcolm, vice president of agriculture and commercial lending with Montana’s oldest bank, the $149 million-asset Bank of the Rockies, said she is concerned about the trade problems and how they will carry over into cattle country.

“We’ll start to feel it this year,” Malcolm said.

Dairy farmers too could feel pinched, as China is a major importer of whey, which is a byproduct of the cheese-making process. The $1.5 billion-asset County Bancorp, based in Manitowoc, Wis., is reviewing its book of loans to dairy farmers, analysts at Sandler O’Neill said in a research note Wednesday.

The Trump administration is discussing a new round of $15 billion in aid for farmers to help offset damage from the trade problem. That aid would be on top of the $12 billion bailout package the Agriculture Department assembled last year. While those in rural banking circles say that money helped some farmers bridge the gap, others wonder how much support can be relied upon in the future.

“This is a one-way street, and at some point you come to a stop sign,” Blanchfield said.