The transition away from Libor, the current benchmark for most floating-rate loans, recently got a lot easier for the CLO market with the recommendation of a forward-looking term rate by a key deliberative body, but important questions remain.

On July 29 the Alternative Reference Rate Committee (ARRC), sponsored by the Federal Reserve and comprising a range of financial market participants, formally recommended a forward-looking term structure for the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR), the regulators’ favored Libor replacement rate. In comments over the last year, regulators suggested restricting such a rate to financial markets where that forward look is essential to their operation, a condition that would exclude commercial lending.

A potentially thorny scenario

Had that restriction been put into place, loans would have had to be priced over the overnight SOFR rate. Interest payments calculated over the term in question would have needed to use one of four methodologies. Commercial borrowers and many lenders worried that such an arrangement would be operationally complex, and the final rate to pay wouldn’t be known until nearly the end of each term, making it harder to forecast future cash flows. Consequently, attentions turned last spring to the Bloomberg Short-Term Bank Yield Index (BSBY) and other emerging Libor-replacement rates offering forward-looking term structures, potentially resulting in a fragmented floating-rate market.

Such a scenario would present potentially thorny complications for CLOs. Regulators want all new transactions to be priced over a Libor-replacement rate starting in 2022 and all legacy transactions by July 2023. So CLOs could end up holding loans priced over a variety of largely untested and differently structured Libor-replacement rates, increasing operational and basis risks.

That could still happen, since the ARRC’s recommendations carry significant weight but are not official regulatory requirements. However, a forward-looking term SOFR should greatly facilitate transitioning the huge volume of legacy Libor loans with similar term structures. In addition, many commercial loans already prioritize term SOFR as a fallback rate when Libor ends, and federal regulators and big banks favor it.

“That sort of certainty allows people to plan and work out the details—amending language if they need to, refinancing, figuring out maturities, etc.” said Daniel Wohlberg, a director at Eagle Point Credit Management. “It leaves less doubt as to what happens with these legacy contracts.”

A migration issue

J. Paul Forrester, a partner at Mayer Brown, said the primary issue for CLOs will be migrating the underlying loans away from Libor before July 2023. Managers will have to coordinate the transitions of the underlying loan portfolios and the CLO securities, and investors will have to bear the resulting basis risk or hedge it, although such hedges do not yet exist and may be relatively expensive.

Another consideration, Forrester said, is that some CLO indentures may have triggers requiring the transition of a CLO’s securities to a replacement rate even before the 2023 deadline. This could happen in existing deals if, for example, collateralized loans priced over a replacement rate reach a majority of the loan pool, thereby creating unexpected basis risk.

“CLO market players would do well to think carefully about Libor replacement structures in CLO indentures over the next few months that could limit basis risk over the next two years,” Forrester said.

Specific to operating CLOs, the transactions must undergo interest-coverage tests, requiring trustees to measure whether the interest from the loans exceeds that from liabilities, and by how much, said Meredith Coffey, executive vice president and co-head of public policy at the Loan Syndications & Trading Association (LSTA).

“If you don’t know your interest rate until the end of the term period, that process becomes more complex,” Coffey said. “Things like that make term rates useful.”

Taking decisions day by day

Few loans have been priced over any of the Libor-replacement rates at this point, and while the large syndicated loans that end up in CLOs are anticipated mostly to use term SOFR, some may opt for daily SOFR depending on borrowers’ needs. Others may choose BSBY or another alternative rate that, like Libor, incorporate credit risk when there’s market stress, something SOFR does not do.

“We don’t know yet for certain what base rate new deals will be issued with,” Wohlberg said, noting that so far there’s been little indication of broadly syndicated loans coming to market imminently that are priced over any of the Libor replacements. “We’re watching the push and pull between the borrowers, lenders and sponsors, the entities closer to the day-to-day accrual and payment of these interest rates.”

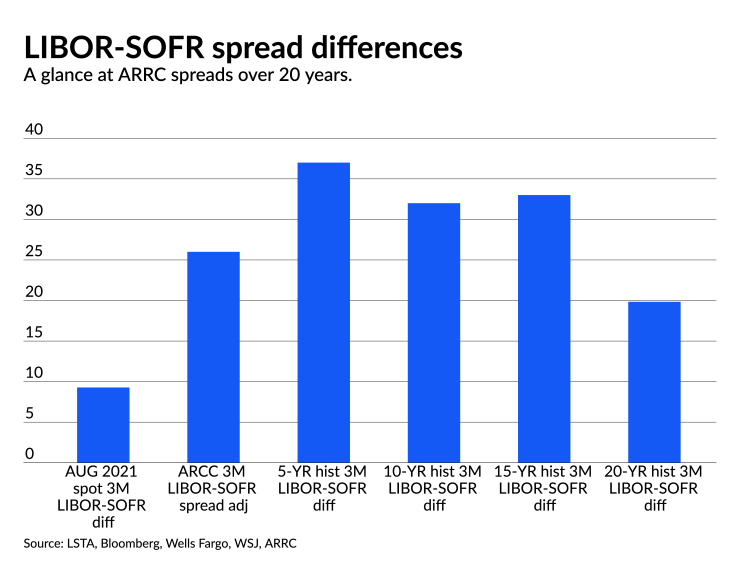

Any hesitation to adopt term SOFR may stem in part from the historically low rate levels of SOFR and the three-month Libor, which most syndicated loans price over. The “spot” spread differential between them is only about nine basis points, while historically it has been much wider because SOFR is a risk-free rate and Libor incorporates bank credit risk. To account for that difference, the ARRC recommends applying a 26-basis point spread adjustment for three-month Libor contracts, based on the two rates’ historical relationship over the last five years, when loans transition away from Libor in 2023.

“The difference between the lower spot spread differential and the higher ARRC recommended spread adjustment can create tension between lenders and borrowers,” Coffey said. “The ARRC’s spread adjustment is the one that is more consistent historically, but borrowers might not care and may want to pay the lower spot spread.”