WASHINGTON — Before Alex Biviano was hired as a server by a popular restaurant chain, his prospective employer sought details about his credit. To provide the information, Biviano paid what he thought would be just a $1 fee to TransUnion to see his credit report. But the process ended up costing him a lot more, he says.

Biviano alleges he was deceived into enrolling in TransUnion's $20-per-month credit monitoring plan. He is among over 100 consumers who recently have complained to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau about being unwittingly enrolled in services offered by one of the three credit bureaus that they say they never wanted.

The charges, which are public on the CFPB's complaint database, have alarmed consumer advocates. They say the data suggests the credit bureaus — most notably TransUnion — have resumed questionable disclosure practices already identified in prior enforcement actions that effectively trap unknowing consumers into expensive plans they never sought.

“I felt scammed, honestly,” Biviano, a 20-year-old college student from Spokane, Wash., said in an interview. “I lost my mind.”

After TransUnion refused to refund him for the first month of the monthly credit monitoring subscription service, he says, Biviano used Twitter to express his frustration.

“PSA: If

At least 86 people this year alone have filed complaints with the CFPB saying they had been for charged a fee for TransUnion's monthly credit monitoring service but that they didn't recall signing up for the service. At least 27 made similar accusations against Experian, and four similar complaints were filed against Equifax, according to the CFPB data. Many of the complainants said they felt scammed or deceived, with some even alleging fraud.

'I can't imagine that was an accident'

Consumer advocates and some of the complainants are pointing their finger at company disclosures that they say are nearly undetectable. The credit bureaus do disclose to consumers that trying to access a credit report means signing up for a monthly credit monitoring service unless they cancel their account. But scores of consumers apparently miss the fine print.

Meanwhile, the complaints against the credit bureaus come amid signs that consumers do not know they are entitled to a free credit report through a website operated jointly by the three companies.

Several consumers claimed that it took months before they even realized they had unintentionally subscribed to a credit monitoring service, racking up charges of as much as $500. Some even said the monthly charge caused them to overdraw their bank account.

One consumer, a 26-year-old man who asked not to be named because he works in politics, told a similar story of seeking a free annual credit report from TransUnion before applying for a credit card. He ended up being charged a monthly fee of $25 for the credit monitoring service, he says.

“Obviously you need to read more and I’ll fully admit that there was some fault in my own part there, but I think it’s also incumbent on these companies to not have deceptive or poorly designed pages," he said. "I can’t imagine that was an accident."

TransUnion initially refused to refund his money, but after he continued to press, it eventually reversed the charge.

“At the end of the day they did the right thing,” he said. “That was because I was irritating and persistent enough to follow up. Ninety-nine percent of people will not be like that, and that’s kind of the game they play.”

In a statement, a TransUnion spokesman said the company's disclosures are clear. "Free tools are clearly labeled as such on our website, and fees for paid services are disclosed clearly and prominently," he said.

But others said those disclosures are so small that they are often overlooked.

"Yes, they do disclose that the consumer is signing up for a trial and that they’re going to be charged, but they do it in teeny-tiny print," said Chi Chi Wu, an attorney at the National Consumer Law Center.

She said disclosure problems previously got the credit bureaus in hot water, but not enough to eliminate the practices for good. "You would think after all the scrutiny, enforcement actions, public anger, being hauled before Congress and grilled for four hours, you think they would be suitably chasten and stop doing this," Wu said. "But they still do it.”

But other observers argue that the credit bureaus are not intentionally trying to deceive consumers, and those who feel misled are missing important disclosures on the side or the bottom of a web page. They also note that a consumer going through the process of accessing a credit report likely has to provide credit card information.

“I don’t know what else you could possibly do to make it more clear,” said John UIzheimer, a consultant who formerly worked at FICO, Equifax and Credit.com.

Regulatory pushback

The credit bureaus have faced regulatory scrutiny for their practices related to free and paid services practically since the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act was passed in 2003. But critics argue that multiple enforcement actions have not led to sufficient reforms.

In 2005, the Federal Trade Commission took action against Experian, claiming the company was deceptively marketing “free credit reports” without sufficiently warning customers that they would be charged for a credit monitoring service if they didn’t cancel a free trial within 30 days. Experian was required to pay the FTC $950,000. Two years later, Experian was fined another $300,000 for violating the earlier settlement.

When asked, an Experian spokesman did not provide details on what the company has done since the 2005 and 2007 settlements to better inform consumers that they would be charged for a monthly credit monitoring service.

“Wherever there is an offer for a paid Experian subscription product, that is noted clearly and conspicuously,” the company's spokesman said.

In 2017, the CFPB

That order required both companies to obtain the “expressed informed consent” of consumers before enrolling them into a credit-related subscription, and also required that TransUnion and Equifax “provide an easy way to cancel products and services.”

Equifax said in a statement that the company has “numerous blog posts and articles” about the right to a free annual credit report. Equifax also links to

TransUnion's spokesman did not provide a response when asked what it has changed since the 2017 order.

“It’s remarkable that they have not reformed their ways and this to me indicates a problem — a fundamental problem of why the credit bureaus continue to be such a huge problem,” Wu said. “And that’s because they just continue to engage in deceptive and unfair conduct even after they’ve been slapped on the wrist, because that’s in their culture.”

Lucrative business

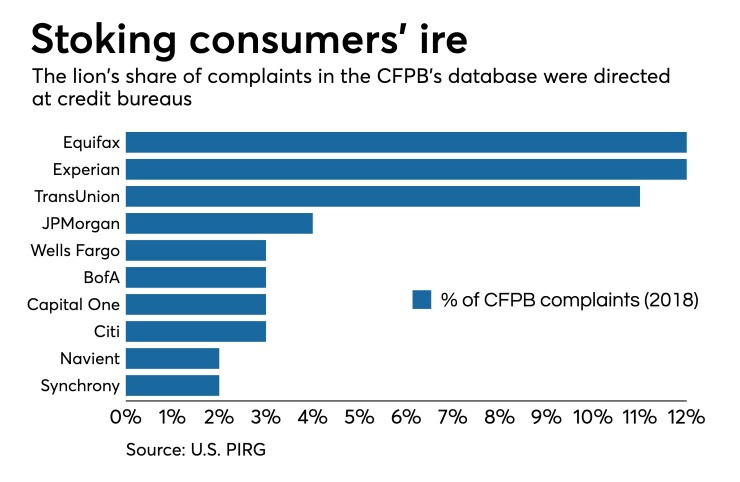

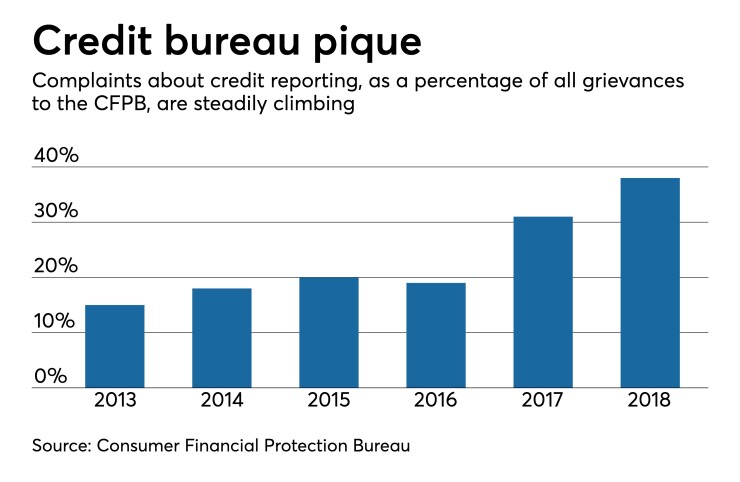

In 2018, credit reports were the most-complained-about product in the CFPB’s complaint database, and Equifax, Experian and TransUnion were the most-complained-about companies.

CFPB complaints specifically related to credit or consumer reporting jumped 27% from a year earlier, and made up 38% of the agency's database.

Thirty-eight percent of complaints the CFPB received in 2018 were about credit or consumer reporting—a 27% increase from the year before.

Most of the CFPB complaints about credit reports pertain to incorrect information on a report. Meanwhile, in general, the agency identified 1,100 total complaints last year about credit monitoring or identity theft protection services offered by the financial industry.

This year, complaints about credit reports are up 18% from the same period a year ago, according to an analysis from Inside Mortgage Finance. In the third quarter, complaints about credit reports made up more than half of total CFPB complaints, and even exceeded the number of complaints about credit reports during the quarter that the massive Equifax data breach was made public.

Ed Mierzwinski, senior director of the federal consumer program at U.S. Public Interest Research Group, or PIRG, said the credit bureaus are likely making money “hand over fist” through credit monitoring services largely because it costs them almost nothing to provide those services.

Deceptive practices are "still happening because the credit bureaus insist on making money when they don’t deserve to," Mierzwinski said. He added that "the CFPB has the authority to fine the banks or the credit bureaus immediately" for misleading consumers into unwittingly subscribing for services.

Wu agreed that the credit monitoring subscriptions are lucrative for the companies.

“You think millions of consumers, $25 a month — that’s a lot of money,” she said.

Yet Ulzheimer said if people are inputting their credit card information, they should expect to be charged for something.

“I guess at some point you have to treat adults like adults,” he said.

However, a number of complaints in the CFPB’s database suggest that consumers believe that the credit bureaus ask for their credit card information in order to verify their identity.

The 26-year-old who works in politics said he assumed TransUnion asked for his credit card number as “either means of identity verification or to check who you are.”

But even if a customer does not read the terms of an agreement, that contract is still legally enforceable, said Caroline Womack, an associate at Morrison Rothman LLP.

“While these business practices are arguably a bit shady, it is the duty of the consumer to know the terms to which they are binding themselves, as well as the consequences of giving credit card information out on the internet,” she said.

Free credit reports are required by law

U.S. consumers are entitled by law to a free credit report from each of the three major credit bureaus every 12 months, which can be accessed only through

But it appears that consumers might not be aware of that right, or where to go to access their free annual credit report.

In a 2012 study, the CFPB found that about 15.9 million people had gotten free annual credit reports from

Unless a person were to type in the exact URL for

For example, Experian owns and operates the similarly named URL,

Such marketing practices are not in violation of the Fair Credit Reporting Act, nor is it illegal if the companies do not readily direct consumers to the joint free website.

An Equifax spokesperson said the company has promoted the free website regardless of legal requirements.

“While there are no prescriptive requirements in the FCRA on how Equifax is required to promote a consumer's right to a free annual credit report,

But in other cases, a customer may not know where to look for the free option.

TransUnion, for one, has various icons that look like they might lead a consumer to

The company's spokesman said consumers have multiple options for getting a free credit report.

"Aside from working directly with TransUnion, consumers are always able to receive a free credit report from

But Mierzwinski said screen shots of navigating through the companies' websites "represent a clear explanation of how the bureaus muddle their descriptions of your rights."

“TransUnion should make it clear that everyone, everywhere, is subject to a free annual report federally and that there are several other circumstances where federal law provides free credit reports,” he said.

No obligation to the public

Ulzheimer found it surprising that people wouldn’t know to go to

“Maybe if a consumer is really disconnected,” he said. “It’s been pretty well communicated by the media. … I guess I feel bad for people who are being charged for those things," but "it underscores the importance of reading the fine print.”

Womack suggested that consumers need more education on their free annual credit reports and how to access them. She also noted that it would be very unlikely that a court would find one of the credit bureaus in violation of any federal law for any of these practices.

“Simply informing the public about where they can go to actually get their yearly free credit report would make a huge difference in whether or not people would get tricked by this sort of stuff,” she said.

Still, “these companies do not have an obligation to the public, even if they should,” said Womack.

But Wu said the onus is on the credit bureaus to inform their customers of their rights.

“You can’t blame consumers. That’s blaming the victim,” she said. “There’s a website you go to:

The 26-year-old who works in politics said that while he knew he was entitled to a free annual credit report, he did not know about

“I would consider myself well-educated. I work, I have a college degree … [and] just the fact that I don’t really know this off the top of my head probably suggests we have a larger problem,” he said.

Solving the problem

Yet there is not widespread agreement about how to improve the process for access credit reports. Some believe lax regulation is to blame, while others believe better financial education or substantial reforms of the credit bureaus themselves are the answers.

The credit bureaus “haven’t faced real consequences, even though they’ve been fined,” said Wu.

Mierzwinski says that there might be less confusion if the CFPB were “policing the marketplace aggressively.”

“They’ve got their big consumer complaint database that they can use to surveil the marketplace,” he said. “The fact that they can impose penalties for the first offense is a pretty powerful tool, but so far the companies have gotten away with this.”

The CFPB declined to comment on the record for this story.

In the absence of CFPB action, Mierzwinski said he looks to Congress to improve the system.

“Congress can strengthen and clarify how to market credit monitoring and make it more explicit what is unfair and deceptive, because the unfair marketing now is basically considered under unfair and deceptive definitions, and those definitions are subjective,” he said. “So if Congress could maybe come up with a strict rule, that would be better.”

House Financial Services Chairwoman Maxine Waters, D-Calif., introduced the Comprehensive Consumer Credit Reporting Reform Act in May, which, among other things, would completely ban “misleading and deceptive marketing” practices, and specifically the practice of automatically changing free trial periods into paid subscription services.

Under her legislation, the credit bureaus would be required to offer explicit opt-ins at the conclusion of a free trial period.

But in the absence of any real action, Biviano, the 20-year-old from Spokane, has been found other resources besides the credit bureaus to get a sense of his credit standing. He said he checks his credit regularly through Discover, and looks at third-party companies like Credit Karma and NerdWallet that give users a glimpse into their profile as the way of the future.

“There are actually a lot more good companies coming out there. The credit reporting industry has always seemed very sketchy, but nowadays there are a lot more good companies,” he said. “They’ve been very good to me … but TransUnion kind of gives them bad names.”