Rising delinquencies in subprime auto lending predictably have drawn comparisons to the mortgage meltdown of nearly a decade ago.

But to get a clear understanding of what is unfolding in the increasingly embattled subprime auto sector, it actually makes more sense to look back two decades, to the 1990s.

At that time, the opportunity to earn high yields by lending to car buyers with low credit scores sparked a rash of competition. The upstart lenders used the securitization markets to expand rapidly. Over time, underwriting standards deteriorated, and more subprime auto loans started to go bad.

Over the past several years, that same market dynamic has been replaying, as analysts at Moody's Investors Service predicted in a June 2012 report.

"The subprime auto lending market is exhibiting some characteristics last seen during the early- to mid-1990s, when overheated competition led to poor underwriting and drove unexpectedly high losses that put many smaller lenders out of business," the Moody's report argued.

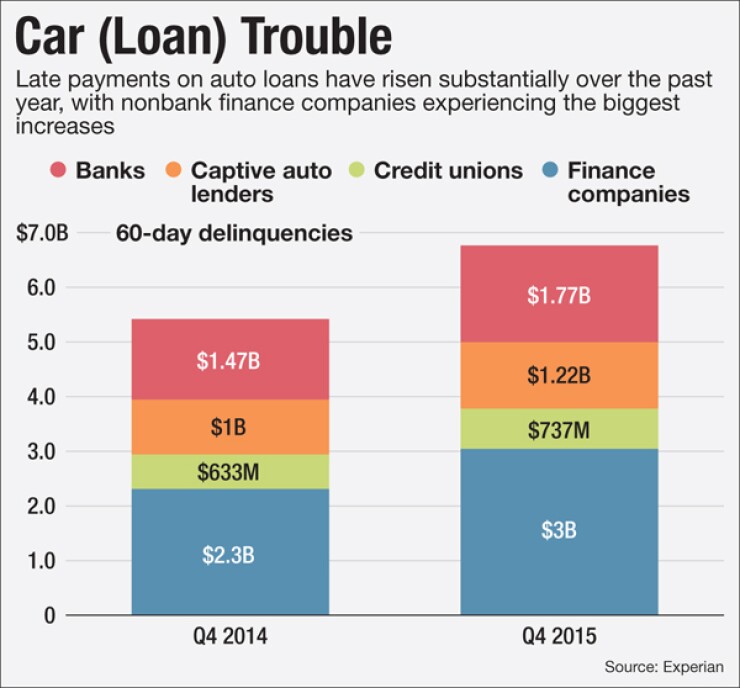

The prophecy seemed fulfilled when this week Fitch Ratings announced that the 60-day delinquency rate on an index of securitized subprime auto loans had hit its highest level since 1996.

In February 5.16% of securitized subprime auto loans were at least 60 days past due, according to Fitch. That slightly exceeded the level of late payments at the height of the Great Recession.

"You force money into a market like subprime auto, and it always ends in tears," said Christopher Gillock, managing director at Colonnade Advisors in Chicago.

Lenders coping with higher-than-expected losses on their securitization deals include Skopos Financial and Exeter Finance, both of which are backed by private-equity firms.

In a $300 million Exeter securitization from October, the average borrower credit score was 573, and 6.6% of the loans went to borrowers with no credit score at all. By December, 5.2% of the loans were already at least 60 days delinquent, according to Standard & Poor's.

During a period when investors have been desperate to find high-yielding assets, nonbank lenders backed by private-equity firms have tapped into the bond markets to achieve rapid growth.

For example, Exeter's portfolio grew to $2.8 billion from $150 million in three years, as the Irving, Texas, company beame the nation's third-largest issuer of subprime auto bonds.

With increased competition, many lenders have lowered their underwriting standards. For subprime loans, the average loan term reached 72 months during the fourth quarter, according to Experian.

Longer loan terms make it easier for borrowers to meet their monthly obligations, but they also mean that repossessed vehicles are worth less on average. The industrywide ratio between what borrowers owe and the value of their vehicles has also been on the rise.

Today, newer entrants into the market are facing bigger challenges than more established lenders that do not rely as heavily on the securitization markets.

"Some newer players to the market are representing a higher share of issuance, and they have higher losses," said Amy Martin, a senior director at Standard & Poor's.

Gillock predicted, "Some of them will fail, because that's what happens when you have a lot of people who enter at the same time."

But any shakeout in subprime auto lending is expected to have far more limited ripple effects than the subprime mortgage fiasco did.

In 2006 alone

In addition, only about 15-20% of subprime auto loans are securitized, according to Standard & Poor's. Capital One Financial and Wells Fargo are among the market participants that do not use securitization.

The subprime auto boom and bust of the 1990s did not destabilize the U.S. economy, and it is largely forgotten today. But it did end with losses to bondholders and a contraction in the number of lenders.

Then, as now, the securitization markets had made it easy for lenders to grow rapidly. By 1997 the number of subprime auto lenders had jumped from just a handful of companies to more than 30, according to Moody's.

The stiffer competition led to looser lending standards and higher losses. Net losses jumped from less than 3% in January 1995 to more than 10% in December 1997, Moody's found.

Eventually, the elevated losses made it difficult for some subprime auto lenders to fund their businesses.

"High loan portfolio losses led to a loss of confidence by investors and lenders," the Moody's report stated.

"This funding crisis contributed to the consolidation of the industry. From 1997 to 1999, 12 subprime auto loan originators filed for bankruptcy and 11 exited the business; other lenders acquired another 18."

Some observers argue there have been important changes in the subprime auto lending business since the 1990s that offer more protection for today's investors. For example, they note that advances in technology make it easier for lenders to repossess vehicles much more quickly after borrowers default.

In addition, today's lenders do more legwork to verify borrowers' income and employment, and to confirm that vehicles actually meet their purported specifications, according to Chris D'Onofrio, a senior vice president at DBRS.

Those steps are designed to improve the chances that borrowers will make their payments, and also to ensure that lenders have adequate protection when loans do go bad."So there's a vast array of things that get done today that were not done in the early '90s," D'Onofrio said.

Still, some observers worry that the situation could deteriorate further if jobless claims start to rise, or if fuel prices rebound. The damage caused by the subprime auto bust of the late 1990s was limited by the strong U.S. economy of that era.

Today, the U.S. unemployment rate sits at 4.9%, its lowest level since February 2008. Initial unemployment claims are also finally back to pre-crisis levels.

What is more, nationwide gas prices, which ranged between $3-$4 per gallon during most of 2013 and 2014, sat at $2.06 per gallon this week. Low prices at the pump have made it easier for many borrowers to afford their monthly car payments.

A drop in used-car values would put additional pressure on subprime lenders because they would take bigger losses on defaulted loans. The Manheim Index, which tracks the value of used vehicles, fell in February by 1.4% compared with a year earlier. But the index still remains quite high by historical standards.

"It's time to be cautious. It's time to start pulling in your sails," Gillock said.

Then he added: "It's not a business for sissies."