Middle market CLOs once played a limited role in the financing of below investment grade companies.

But a growing number of asset managers are waking up to the opportunity created as bigger banks cut back on lending to small and medium-sized businesses. Middle market loans are increasingly popular with investors because they pay floating rates of interest and are higher yielding, and often better underwritten, than loans that are originated by banks and broadly syndicated.

More of this direct lending is making its way into the securitization market.

In the last two months, private equity firms

GSO/Blackstone and Bain join what had been a clubby market comprised of asset management firms including The Carlyle Group, Golub Capital and Churchill Asset Management that both securitize loans made in-house, via middle market CLOs.

(Golub and Carlyle also acquire loans to large corporate loans in the “open market” and securitize them via broadly syndicated loan CLOs.)

“For businesses that have robust CLO franchises, and have a robust direct lending franchise, it’s kind of natural to pursue something in middle market CLOs,” said Michael Herzig, a managing director with THL Credit, another firm that provides direct lending to lower middle market firms (under $50 million annual EBITDA) via first- and second-lien loans as well as unitranche investments.

THL, a regular issuer of BSL CLOs, has yet to issue a middle market CLO deals.

Large asset managers aren’t the only sponsors of middle market CLOs. Business development companies, a kind of closed-end investment fund that specializes in middle market lending, are also regular issuers. Securitizing loans on their balance sheets frees up capital to put back to work, allowing them to skirt regulatory restrictions on investing with borrowed money.

And while middle market CLOs are still subject to risk retention, a recent ruling from the SEC gives them another option for complying with skin-in-the-game rules.

Through mid-September, $11.6 billion of middle market CLOs had been issued, putting the market on track to beat the $14.5 billion issued for all of last year and the $8.4 billion issued in 2016, according to Thomson Reuters LPC.

Banks started pulling back from middle market lending as early as the 1990s, when they were freed from Glass-Steagall restrictions on investment banking. Restrictions on lending to the riskiest companies introduced by banking regulators in 2014 made it even more attractive for banks to arrange wholesale financing, leaving nonbanks to make the loans, service them, and manage the risk (in some cases, via securitization).

“Wells Fargo does not do a tremendous amount of lower middle market sponsored direct lending today, but Wells is a very active provider of financing to leading middle market managers like Churchill who do,” said Ken Kencel, Churchill’s president and CEO.

In a white paper published in April, Ares Management estimates that banks now hold just 9% of loans to below investment grade companies of all sizes, down from 71% in the 1990s.

Scramble for market share after GE bows out

Initially, GE Capital picked up much of the slack, making loans and funneling them through its GE Antares unit. But in 2015 GE sold the direct lending business (now Antares Capital) to the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board for $12 billion, a move designed to help shed its designation as a systemically important financial institution. GE's exit opened the door for competitors like Golub, Monroe Capital and Newstar Financial as well as newcomer Churchill , which was acquired from Carlyle Group and established as a standalone asset-management platform through TRIAA-CREF affiliate Nuveen.

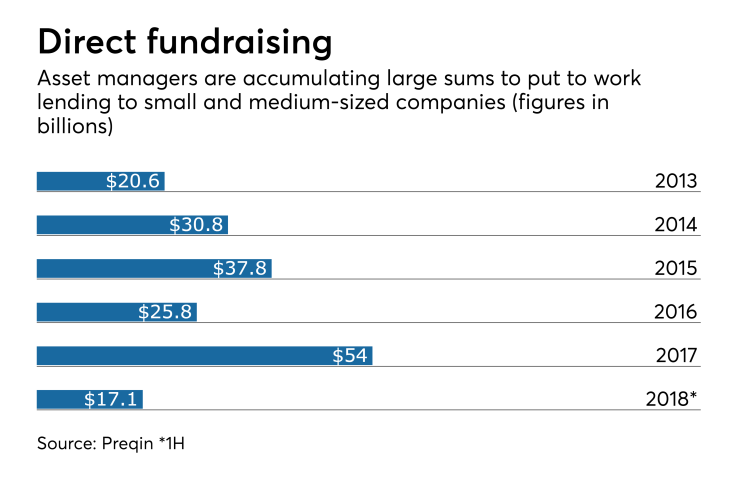

Last year more than $54 billion was raised for direct, or nonbank, lending, to small and medium-sized companies, according to Preqin.

Through the first half of 2018, fund closings this year lagged last year’s pace at $12.9 billion – but Preqin estimated that at the start of the second quarter, 47% of the $160 billion in capital being sought by 350 global funds is focused on direct-lending needs.

In July, Blackstone’s GSO Capital Partners reportedly said it plans to raise $10 billion equity and debt capital through next year to lend to middle market companies. The announcement came just seven months after it mutually agreed to end a BDC partnership with FS Investments.

FS Investments has since teamed up with KKR; together they have raised $18 billion to put to work in the middle market through a joint business development company to be merged from each firm's existing publicly traded BDC.

Carlyle Group was one of the first private equity firms to get into direct lending, in 2011; middle market debt now accounts for $3.5 billion of the $36 billion in assets under management for Carlyle’s global credit unit; the firm hopes to raise another $1 billion by the end of 2019.

Direct lending has become predominant source of the $87 billion in assets that Ares Management runs in its credit unit; and that unit dwarfs the $24 billion Ares has in private equity funds and the $11 billion it has in real estate funds.

Apollo Global Management has been on a four-year spree of acquiring direct lenders and expanding its credit offerings to small businesses. Its Financial Credit Investments Fund was 85% invested as of the second quarter, so the firm is raising money for a second fund, chief executive Leon Black in a conference call with analysts.

To be sure, not all of the middle market loans made by nonbanks are used as collateral for CLOs. Still, the asset management firms that have long worked in the space – and remain the primary issuers of middle market CLOs in today’s market – also plan to expand their direct lending platforms. Guggenheim Securities closed on a $2 billion direct lending fund in the first quarter, according to Preqin.

In its April report, Ares estimated the size of outstanding middle market direct loans held by private funds and asset managers in the U.S. to be $910 billion – nearly three times the $300 million they held in 2012. The report acknowledged that reported data is limited, and likely understates the size of the market opportunity.

“We’ve essentially replaced the traditional commercial banks as the primary providers of senior debt financing to these companies,” Kencel said. “Middle market direct lending has grown dramatically in popularity as investors look for yield.”

It remains to be seen how all of the capital being raised for direct lending will impact yields and underwriting. In August, the average middle market loan spread (including mezzanine, second-lien and blended rates of unitranche loans) was 480 basis points over Libor, compared to 371 basis points for broadly syndicated loans pooled in open-market CLOs, according to Thomson Reuters LPC.

Wells Fargo expects that the increased use of leverage by business development companies alone is likely to depress yields. The U.S. government budget bill that President Trump signed in March included a provision lifting a cap on leverage ratios for these funds to 2:1x. Previously, they could only borrow $1 for every $1 of equity.

In an August report, Wells Fargo said it expects business development companies will only increase leverage ratios to 1.25x, but even that will result in “increased leverage will likely also pressure middle market loan spreads tighter” as middle market CLO managers compete for loan collateral, the report said.

This increased leverage could well come from issuing more CLOs, as opposed to using lines of credit or issuing other kinds of debt, according to Kencel. He noted that the corporate credit ratings of several publicly traded business development companies were put under review for a possible downgrade after the cap on leverage was lifted.

“What they [business development companies] failed to take notice of is that the borrowing costs .... were quite low because the rating agencies were willing to assign them a corporate investment grade rating based on the 1-to-1 leverage limitations,” said Kencel.

Issuing CLOs would allow BDCs to raise money without boosting their leverage ratios, he said.

Potential for decline in credit quality

As middle market lending expands, some worry that the credit quality of the loans will inevitably deteriorate.

Unlike most broadly syndicated corporate loans, the majority of which have few restrictive covenants, middle market loans are closely monitored through maintenance covenants by lenders. And for good reason: middle market lenders either have these loans on their books, or with a CLO in which they hold substantial equity – usually around 50%, according to Kencel.

And if a middle market borrower defaults on a loan, the recovery prospects are much dimmer than on a larger senior loan, said Kevin McLeod, a managing director for Cerberus Capital Management, another direct lender.

If a middle market loan reached a payment-default stage “is far, far too late” to salvage the loan, McLeod said at IMN’s ABS East conference on Sept. 25. “Companies have lost their supplier relationships, their customer relationships, probably their employees. It’s over. After a payment default, recovery is probably going to be abysmal.”

But strong investor interest in middle market loans also makes it easier to issue CLOs with fewer investor protections. Wells Fargo, citing research from S&P LCD, reported a “rise of loan terms historically reserved for BSL loans,” with an increase in EBITDA addbacks and adjustments, delay-draw terms, “stretched-senior” and unitranche deals.

One newcomer in the middle market space, Vista Credit Opportunities, issued its debt CLO with single-industry (software and IT) concentration exceeding 75%, well above the industry exposure in a typical broadly syndicated loan CLO, which is under 10%.

In early September Fitch Ratings called out two of its competitors for assigning triple-A ratings to the Vista CLO. Although the report did not name the CLO, a description of the deal's top-heavy exposure to the software industry, and the reference to the lack of caps on industry exposure, clearly fit the $305 million VCO CLO 2018-1, which priced in August via Wells Fargo and GreensLedge Capital Markets.

Fitch said the heavy concentration in high-tech could

S&P Global Markets and DBRS rated the deal. S&P declined to comment on Fitch’s report.