Shopping centers anchored by supermarkets were once a coveted lending opportunity at TowneBank. While the Portsmouth, Va., bank hasn’t pulled the plug completely on them, its loan officers are definitely having second thoughts.

“Supermarket shopping centers had been an attractive asset class for us for a long time,” said Jeremy Starkey, president of commercial real estate finance at the $8.4 billion-asset TowneBank.

“It’s not as attractive as it used to be,” he said.

Starkey and TowneBank have plenty of company. Bankers at several other institutions with big commercial real estate book have also decided to think twice about loans on strip centers dominated by a large grocery store. There are too many warning signs on the horizon, from the

“My opinion is that this probably represents a structural change in terms of the intensity of online competition for grocery,” said Mike Wilson, chief lending officer at the $4.3 billion-asset Bankers Trust Co. in Des Moines, Iowa.

It’s the latest sign of trouble in CRE lending. Regulators

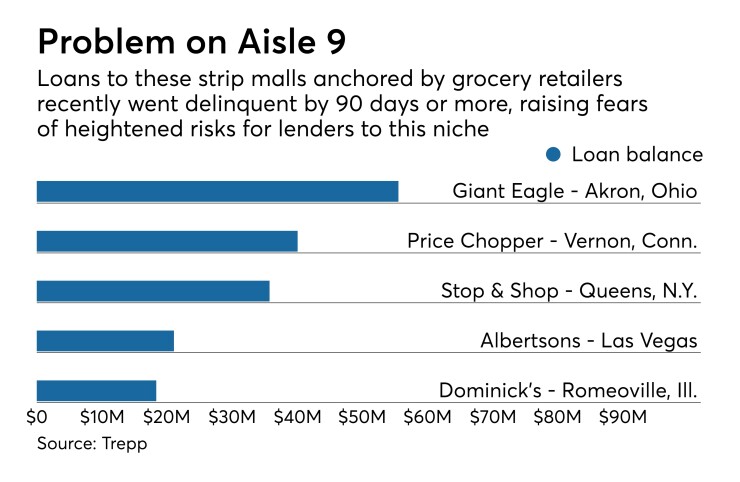

To be sure, the vast majority of CRE loans tied to supermarkets are performing, said Matt Anderson, managing director at the data provider Trepp. But distress signals have popped up among commercial mortgage-backed securities that include large loans anchored by grocery stores.

Credits that were at least 90 days late as of September included a $55 million loan on the Rosemont Commons shopping center near Akron, Ohio, anchored by a Giant Eagle shopping center, and a $40 million loan for a Price Chopper-anchored strip mall in Vernon, Conn, according to Trepp data.

Those types of delinquencies should raise eyebrows among CRE lenders, Anderson said.

“It makes you pause to consider that we’re in the midst of an extended economic recovery, but we’re still seeing these problems,” Anderson said. “There are new problem loans showing up every month” on properties tied to grocery stores, he said.

Because of the nature of CMBS, it is impossible to determine which banks are still on the hook for loans that have been securitized. But if loans included in a security have become distressed, it is a sure sign the same thing is happening to individual CRE loans that regional and community banks hold on their portfolios, Anderson said.

TowneBank has decided to underwrite and originate such loans only for existing customers “that make sense on a case-by-case basis,” Starkey said.

Bankers Trust holds about $1.3 billion of non-owner-occupied commercial real estate loans, the subcategory of CRE loans where banks typically include shopping center loans. However, Bankers Trust does not have “significant exposure” to the supermarket sector because “that is a very narrow-margin business that tends to be risky,” Wilson said.

Profit margins in the grocery business have gone from narrow to razor thin. Earlier this year, Kroger, the largest U.S. supermarket chain, posted two consecutive quarters of declining same-store sales, its worst slump in more than a decade. Its profit margin plunged below 1% in the second quarter.

Some supermarkets have shown even greater signs of stress. Marsh Supermarkets in Indianapolis

Plenty of banks have originated loans for either the development of grocery-anchored shopping centers or refinanced those loans. Grocery-anchored real estate represents the largest part of the retail loan portfolio at the $22 billion-asset Iberiabank in Lafayette, La., Chief Risk Officer Terry Akins said in a July 21 conference call. He did not break out specific figures, and banks are not required to disclose their exposure to the grocery sector.

The $36 billion-asset East West Bank in Pasadena, Calif., is an active lender to grocery-anchored shopping centers. But East West believes it adequately manages its risk because many of its CRE loans are to developments that serve ethnic communities and which include lots of small stores, which spread out the risk, Greg Guyett, chief operating officer, said during a July 20 conference call.

But a growing number of bankers seem to be taking a standoffish approach to supermarkets and the entire retail sector in general. Apparently, Amazon and online commerce pose such a threat to traditional retail that many real estate lenders have decided to sit on the sidelines.

“The retail we do are in strip malls in Brooklyn and Queens, maybe a small food store or restaurants, where there’s a lot of walk-in traffic,” said John Buran, CEO at the $6.3 billion-asset Flushing Financial in Uniondale, N.Y. “We’re going to have very little exposure to retail, including large food stores.”