Brazil is one of the brighter spots in global ABS, a different world from the regulatory anxieties, debt overhang and slower origination plaguing other countries.

On the face of it, it is a poor climate for distressed-debt players. And there are other, more deeply seated reasons why this field is small in Brazil in the first place: protracted bankruptcy proceedings, pro-debtor bias in courts in recovery efforts, sellers loath to dump their bad assets and a flimsy secondary market, among others.

Still, small pockets of ABS have gone south over the past few years, while trouble is brewing in niche areas, potentially gestating opportunities for distressed players. And plenty of originators already hold soured assets on their balance sheets in an economy that is, by the IMF's reckoning, now the world's seventh largest.

The few players already active in the field certainly see opportunities in the near and long term.

The FIDC

Brazil's endemic securitization vehicle, the FIDC, is ideal for packaging distressed assets, players said. This fund-SPV hybrid has a number of advantages over the alternatives.

"It's the ideal structure from a regulatory standpoint, a fiscal standpoint and in terms of efficiency for a fund manager," said Oscar Decotelli, a partner at Vision Brazil Investments, an investment manager with about R$1.1 billion ($691 million) of current net asset value in distressed credit situations. "[The FIDC] is like a CLO that's gone well - they're listed, have daily NAVs, and you're able to structure a correct way of having a senior and subordinate tranche."

As ABS pros in Brazil are always quick to point out, the tax incentive for using an FIDC is sizable. The sort of FIDC that's used for distressed assets is known as "nao-padronizado," or non-standardized. This precludes some retail funds from buying in.

Decotelli said that he has also used, for real estate assets, the vehicle known as the CRI, akin to a CMBS or RMBS.

There is, of course, not a single strategy for using a FIDC as a way to monetize distressed assets. Velum Credit Management, which is an investment consultant for two FIDCs in Brazil, will drop assets into a fund around the time they are purchased, said Fabiano Ramos, CEO of this distressed-focused outfit, which handles about 5.2 million accounts representing R$3.0 billion in face value.

"We just call investors and have the FIDC capitalized," he said. "I can use the money within 180 days." Velum has a consumer focus, though it will look at corporate assets opportunistically.

Vision, for its part, typically has the FIDC ready but will sell the shares to the market once the underlying assets are more "mature." "We believe that you can put the assets into the FIDC, but once the company's going toward a more advanced stage, when they're safer, then you sell [the shares] to the market," Decotelli said.

Another investment manager in the business, Root Capital, recently took over Union Capital FIDC Financeiros e Mercantis - a factoring-backed deal that notoriously blew up earlier this year. While Root is open to working with other FIDCs that have fallen from grace, "our focus now is the launch of new funds," said Rafael Fritsch, the firm's CIO.

Getting into Trouble

Just where these players look naturally depends on the willingness of sellers to part with their assets.

Their reluctance to do so, according to Ramos, is a major obstacle in sourcing distressed assets in Brazil, particularly in the banking industry.

The top five banks in Brazil - which have a combined asset-market share of more than 2/3 - have generally shown little interest in shedding bad assets. Giants Banco do Brasil (BdB) and Caixa Economica Federal present their own particular set of bureaucratic obstacles as state-owned banks, Ramos said. BdB actually has a unit, Ativos, that is a holding tank for the bank's bad assets, but it has not shown much interest in playing with others.

Ramos said Ativos has well above R$30 billion in assets. "It's government employees, and they have their own agenda. It's difficult for Ativos to sell portfolios."

Decotelli said there was currently an auction of a nonperforming loan pool from a large bank, but he noted that that sort of activity is relatively new. "You still need to have your contact with small and large local banks, smaller [corporates] and hedge funds that need to wind down their positions," he said.

Another reason that the larger banks are not anxious to shed distressed assets is that they have plenty of room to keep them on balance sheet before feeling pressure from Basel rules, according to Ramos. Many smaller banks are hitting the limits, but they have been rescued by the FGC, an institution akin to the resolution trust corporation of the FDIC. "Basically the FGC is capitalizing the banks," he added.

The secondary market for distressed assets is "very poor," said Root Capital's Fritsch, who used to run a distressed fund in London. "[And] it's a business that should exist in any market in the world."

The reluctance of Brazil's larger banks to sell their bad assets also stems from concern that while they would cede control of collection procedures, they might still remain vulnerable to potential legal action by debtors. "It's possible that the debtor ends up suing both the current holder of the claim as well as the original lender," Ramos said, although he added that these kinds of worries on the part of sellers are overblown.

Poorly executed deals in the distressed market in the past are partly to blame for the cautious approach by many originators, players said. "You have people that would come in, buy at a deep discount and put everyone on the credit bureau, and that would suffice," Ramos added. "That created a lot of headaches for everyone."

See You in Court

Litigation plays an oversize role in this sector, more so than in the distressed assets in other countries.

The pro-debtor bias that many perceive in the legal system has kept the sector small in Brazil. A bankruptcy law from 2005 that was only really tested in 2009 has been an improvement, said Vision's Decotelli. But, he added, how a court is likely to rule is strongly influenced by the state in which the case is heard and the type of company with the liability in question.

For instance, courts in the interior of the country are less prone to respect an FIDC than those in the states of Sao Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, sources said.

"Most of the lawsuits we have are related to the non-recognition of the FIDC as the creditor, even though we have sent a notification to the debtor, with a copy of the contract and so on and so forth," said Ramos. "It's very different from in the U.S."

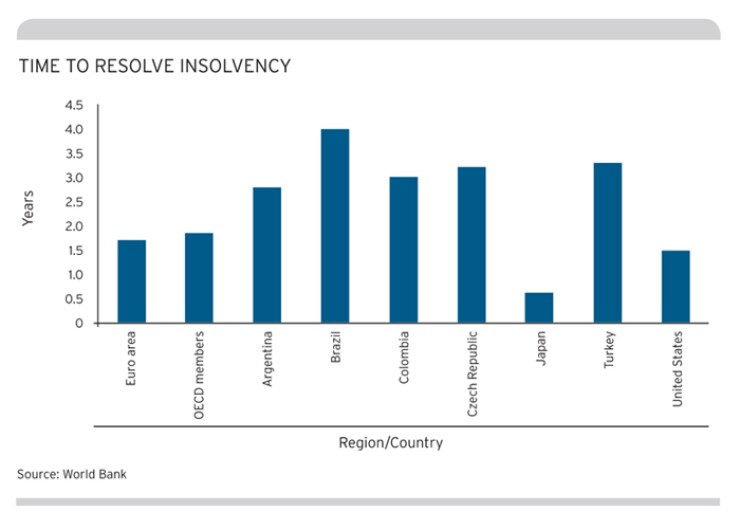

Even when there is some confidence that the ruling will go the way of the creditor, the length of time for a case to be resolved can gobble up investment returns. Just how high the legal costs end up in a typical distressed situation can be discerned by looking at the average time it takes to wrap up insolvency as compared to other countries (see table below).

Brazil's figure of four years is higher than most other countries, particularly more developed ones.

Decotelli noted that for most cases since the 2005 bankruptcy law went into effect, the creditor's rights will be ultimately recognized, but it is the duration of the legal proceedings that participants must factor into their expected return and that therefore determine how they will price the asset.

Finding the right law firm is obviously key to the process. Decotelli said that when it comes to handling bankruptcy proceedings for distressed assets, there are a number of boutique shops that do it well. The larger firms more familiar to the global structured finance world tend to avoid this area. "The fighting in the courts - there's a lot of image risk for them," he added.

Sources said the exorbitant legal costs of seeking recovery were unanticipated by foreign banks and hedge funds that bought into higher-yielding FIDCs that went sour over the past few years, such as those in agriculture and factoring. The Union National deal currently managed by Root is a prime example. Backed by factoring receivables and issued in late 2008, the transaction hit a 99.9% provisioning of its credit portfolio by the end of March, according to data from regulators in a report by Moody's Investors Service, which does not rate the deal. Other players have warned about the risks of factoring ABS in Brazil (see ASR 6/2011).

A number of foreign investors were understood to be major buyers in Union National. An investment unit of McKinsey & Company was said to be among them. A spokesperson from the consultancy declined to comment on the matter.

It is unlikely that foreigners who have been mauled in these deals priced in the legal costs should they go sour.

Ramos said that the debtor of an asset owned by one of Velum's FIDCs won a R$20,000 settlement from a judge on a R$165 debt. They are appealing the decision. "If you don't have a very good servicing capability and don't incorporate those risks into pricing, you can get burnt big time," he added.

Where the Bad Assets Are

Which asset classes might be generating opportunities for distressed players depends in part on whether sellers will start to feel more comfortable with offloading their bad assets and will accept the discount these players are willing to pay.

Originators with distressed assets have used the FIDC themselves to take advantage of its benefits. BV Financeira, for instance, issued a FIDC backed by performing and nonperforming vehicle loans from its book in late December. The deal, with a 13-year legal final, was split into R$678 million in senior shares and $399 million in a subordinated piece, retained by Banco Votorantim.

The fund continuously repurchases eligible performing vehicle loans provided that no trigger event has occurred. But the nonperforming loan component is a static pool bought shortly after closing. Moody's rated the senior piece 'A1.br', while the subordinated shares are unrated. In the agency's stress case scenario, cumulative recoveries never exceed 10%, with the bulk of recoveries in the first six months.

Players in the field would probably have more confidence that they could recover something after six months, but Ramos noted that after a year they become much more difficult. For consumer debt, collections become nearly impossible after five years. That is because arguably the biggest stick a collector can wield is to put or keep an individual in Brazil's credit bureau, which cripples his or her ability to borrow. But there is a five-year limit for keeping someone's name listed in the bureau for a specific liability. "So after five years it's very difficult to go after them," Ramos said.

With all the difficulties, it is a wonder that distressed ABS deals in Brazil happen at all. But the players say the opportunities are there - one just has to work a little harder than in a market like the U.S. to ferret them out and price them correctly.

Root Capital's Fritsch said that his firm is keeping an eye on fast consumer loan growth in the banking system. While overall debt remains very low by developed countries' standards in Brazil, the competition for new borrowers has hurt underwriting standards. "Any bank that grows its loan book by 20% a year will have asset quality problems down the road," he said. "Brazil is no exception."

He added that his firm is interested in managing any kind of distressed debt. Root is launching a new FIDC of troubled assets in a couple of months, using in part R$30 million from asset management partner JGP to fund the collateral.

Heady growth in consumer portfolios in small and medium banks calls to mind payroll-deductible loans, a fast-growing segment that has been a popular asset for FIDCs. Vision's Decotelli said the opportunities in this area are harder to come by than a few years ago. His firm managed the first FIDC of payroll loans in 2005.

Ramos said that to get involved in distressed payroll-deductible loans is a "nightmare." He explained that a debtor often stops paying because he lost his job and then may go into the informal sector, where he will be harder to locate. Even if a debtor can pay the debt, he might not feel that it actually is debt in the traditional sense but is instead an agreement entered into with his former employer for which he's no longer on the hook, Ramos said. He added that a major source of these loans is the federal pension system. As these borrowers can be very old, death becomes a major risk factor. Collecting from a deceased employee's family in these cases is virtually impossible.

Decotelli said that government-related distressed situations might create more opportunities for Vision, which has experience in this area. One area of particular interest is "any type of debt-type assets related to mistakes the government made in the past," he said. Often these have to do with debt incurred during the country's hyper-inflation period.

In the past, Vision has managed deals backed by precatorios, obligations that the government, at the federal, state or municipal level, has been ordered by a court to pay to an entity. Often it is generated after a protracted legal drama in which a government contests an alleged debt and loses in court. But the debtor often keeps finding new ways to challenge the claim, even after the precatorio is issued. But the firm has moved away from this sector since 2007, Decotelli said.

A related area where the firm has found value more recently is legal claims against state companies that were generated during the hyper-inflation era.

Agriculture is another sector where Vision is active. The firm had become a major funder of agriculture in the 2006-2007 period and was hit hard by defaults in its portfolio in 2008 that were "significant enough to give us headaches but not enough to kill the business," Decotelli said. The firm is now more selective about its involvement there, with roughly only R$55 million of the R$1.1 billion it manages in the distressed area. "We believe that the yields you get from asset-backed lending there aren't adjusted to the risks you incur," he said. "From the credit standpoint, the opportunities in agriculture we think have somewhat passed."

Ramos said that, on a small scale, tuition receivables from universities might provide distressed opportunities. GP Investimentos completed a R$100 million nonperforming tuition-backed FIDC late last year, he added.

Nonperforming mortgages might also start being securitized next year, he added. "It's growing so fast, we believe next year we're going to see the first stages of selling delinquent mortgages," Ramos said, referring to heady expansion of mortgage origination. For the most part, however, LTVs remain exceedingly low in Brazil. But Ramos said that Caixa, by far the largest mortgage originator in the country, has a unit called EMGEA that holds its delinquent mortgages. The size of its portfolio is estimated at more than R$20 billion.