As titans of entertainment and media resign over sexual harassment charges, many bankers argue that their industry already had its reckoning two decades ago and is largely free of the worst problems as a result.

But scratch beneath the surface, and there is a lingering feeling among many that harassment is not only present, but it may actually be inevitable, based on responses to a new survey that SourceMedia, the publisher of American Banker, conducted across the banking industry, including mortgages and payments professionals.

“The banking community has a frat boy environment that can be hostile towards women,” a male banker in his 30s said in a written response to a survey question.

Also in this series:

A female banker in executive management wrote that “it’s prevalent everywhere because it was allowed for so long.”

Some experts argue that harassment is so entrenched, it will take significant time to root it out, if that is even possible.

Attention surrounding “the issue of sexual harassment is here to stay for the foreseeable future,” said Stephen Hahn-Griffiths, chief research officer at the Reputation Institute.

The mentality that there’s nothing that can be done to eliminate sexual harassment may pose a critical threat to banks and other companies, leading to a vast range of possible repercussions, including litigation, reputational risk and problems with recruiting, experts said. Indeed, reputational concerns are of a particular concern to banks, since they can quickly blossom into a safety and soundness issue. The #MeToo movement has already felled once highflying firms in the wake of revelations that they tolerated an executive's abusive behavior toward female employees.

"The reputation risk is how you chose to handle the situation," said Hahn-Griffiths. "That becomes problematic if not managed correctly or if management takes sides, or there isn’t a fair and equal settlement. It also depends at what level where the harassment takes place. The higher up in the echelon, the greater the risk."

That's why it's critical that banks do not see it as inevitable, experts said.

"It is a learned behavior,” said Jim Quick, a professor of leadership and organizational behavior at the University of Texas at Arlington. “If people have learned these kinds of comments and actions, they can unlearn them. Does the organization have the will and the principle to not tolerate that kind of behavior? That’s the bottom line.”

Scope of the problem

CIT Group Chairman and Chief Executive Ellen Alemany recently drew attention by

Based on the survey results, some others in the industry likely would agree: Forty-one percent of respondents said they have not experienced, witnessed or heard about any harassment in the workplace.

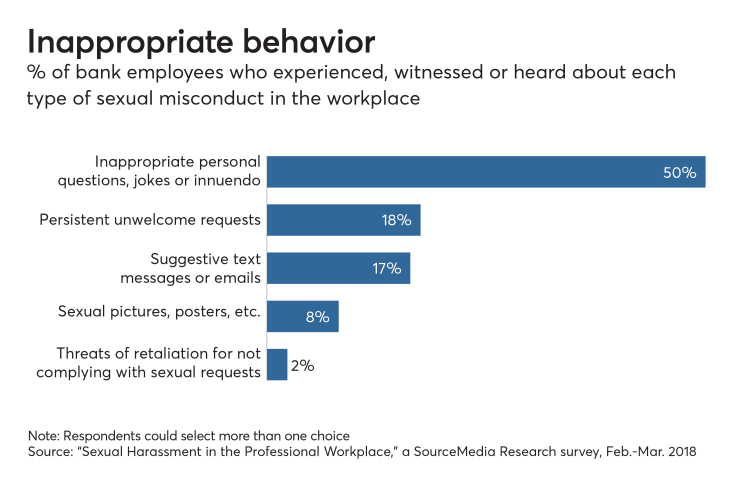

Yet even more said they were at least aware of problems: Forty-three percent know others who have been subject to harassment during their careers. Almost a fifth said they have witnessed misconduct, and 13% said they have been subject to unwelcome sexual advances. That included a range of behaviors, such as inappropriate questions and jokes, lewd texts and threats of retaliation for not going along with the misconduct.

"If you say it is inevitable, you are just giving up before you start."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the responses differ when broken down by gender. Twenty-eight percent of female respondents in the banking, mortgage or payments sectors said they have been subjected to unwelcome sexual conduct in the workplace during their careers. Another 21% of women said they have witnessed sexual harassment while 45% said they said they know of others who have been subjected to such conduct.

(The SourceMedia survey included 414 professionals in the banking, payments, and mortgage sectors. The overall survey, which studied sexual harassment across a range of industries, including health care, wealth management and accounting, received more than 3,000 responses.)

Root of the problem?

In the survey and separate interviews with respondents and others in the industry, many faulted the lack of diversity among leadership as a key reason sexual harassment persists.

“When you look into those crowds of bankers, everyone does look alike,” said Julieann Thurlow, president and CEO of the $549 million-asset Reading Cooperative Bank in Massachusetts.

Women are often reluctant to speak out because of this power dynamic, Thurlow said. “It tends to get snickers rather than a serious, thoughtful response.”

Women in banking may be choosing to remain silent on the subject because they don’t feel they have enough support to voice their concerns, said Ann Marie Painter, a partner in the labor and employment practice at Perkins Coie.

“The desire to remain silent is really strong, regardless of what is going on in other industries,” Painter said. “There are maybe so few women in the banking and financial services industry that they may not be at a level of power and authority that they even feel comfortable coming forward together.”

"I believe it is quite possible to end [sexual harassment] all together."

Despite efforts to diversify in recent years, gender imbalance at banks, particularly in the upper ranks, remains a problem. KeyCorp’s Beth Mooney is the only female chairman and CEO of a top-20 bank. Women made up just 20% of boards and 16% of executive committees at financial services companies in 2016, according to a study from Oliver Wyman.

This imbalance was highlighted in SourceMedia’s survey by numerous respondents as a reason for the prevalence of harassment in the industry. A male banker in his 40s who said that harassment is moderate to high noted it was “not a good combination” to have upper management dominated by men while women serve in the majority of junior positions.

Another banker who works in technology blamed “the overall ‘Wall Street’ culture.”

“Skewed ratio,” “societal norms” and “testosterone and stupidity” were mentioned by other participants as contributing factors.

The industry is “dominated by men and behavior goes unchecked,” said another female banker, who described herself as 26 to 29 years old and working in technology. “Until there are more female executives and pay parity exists, this pattern will continue.”

Dorothy Savarese, president and CEO of the $3.2 billion-asset Cape Cod Five Cents Savings Bank in Harwich Port, Mass., said adding diversity is a key to ending the problem.

“Banks can fight,” she said in an interview. “If you say it is inevitable, you are just giving up before you start. I have been working so hard for years now to encourage diversity, and one of the things we do see is the more women and other kinds of diversity you have at management level, the more open people are to differences.”

Solution to the problem?

Banks have other ways to combat sexual harassment, experts agreed. One of them is simply to reject the notion that the problem is unsolvable.

“Sexual harassment has been around for decades, centuries, probably even longer,” said Davia Temin, the president and CEO of Temin and Co., a management consulting firm that focuses on crisis and risk management. “But just because something has just reached a tipping point and is beginning to change, that doesn’t mean it is inevitable. It just means change has taken a long time to come.”

Leaders must be sure to handle issues appropriately as they arise. If it appears that management is willing to tolerate sexual harassment, then that could actually encourage others to engage in that same behavior. Generally bad actors make up only 1% to 3% of people, but that could spread if management fails to act, Quick said.

“It goes back to culture and if sexual harassment becomes acceptable, then people who normally wouldn’t engage in it may do it, especially if powerful others are the ones doing it,” said M. Ann McFadyen, an associate professor of strategic management at the University of Texas at Arlington. “It may be seen as necessary to fitting in. People just want to fit in with others.”

Management must promptly respond to complaints, quickly launch an investigation and include individuals trained in this area, Painter said. If the process is done fairly and with integrity, that can go a long way in building trust among other employees, Painter said.

In the SourceMedia survey, 36% of respondents in the banking, payments and mortgage sectors said they believe harassment complaints are usually dealt with fairly and appropriately, while 15% said this is always the case, 18% said occasionally, 13% said rarely or infrequently, and 1% said never. Another 17% said they didn’t know.

Treating complaints appropriately is of the utmost importance, experts said. If banks fail to do so, it could prove to be a blow to their reputation, and endanger not just the morale of their employees but outside business.

“If there are public allegations against your bank, then you have lost trust,” Savarese said. “How do your customers know they can trust you? You serve the public. If you have an environment that allows inappropriate behaviors, how do customers know they too won’t be subjected to that behavior? There is every reason from a business perspective to work to prevent sexual harassment.”

The role of leadership

Ultimately, successful handling of harassment lies with the tone set at the very top of the organization.

Harassment “shouldn’t be inevitable,” said Dan Stahl, principal at Human Resources Group. “That is purely a leadership problem and that can be addressed with leadership.”

“In the absence of communication, you are sending a communication.”

The current national conversation about sexual harassment presents bank CEOs with a good opportunity to reaffirm their commitment to a zero-tolerance policy on these issues, experts said.

That means executives should send out a message – through email, video or during a town hall meeting – where they clearly and directly address sexual harassment, said Mike Clement, founder and managing partner at Strait Insights, a communications consulting firm. Failure to do so sends a message of its own, he added.

“In the absence of communication, you are sending a communication,” Clement said. “And in this case the message is you are not taking advantage of an opportunity to re-emphasize your company’s culture and what you consider important. It can have an impact on how employees view the type of company you are.”

Some are already taking the lead. When the #MeToo movement gained steam, Old National Bancorp Chairman and CEO Bob Jones sent out a message to employees that stated that this type of behavior would never be tolerated. The $17.4 billion-asset company

Amarillo National Bank in Texas sent a personal letter from its president, Richard Ware, to all employees affirming there was no place for harassment.

“If upper management isn’t on board, then everyone will think they are exempt from it,” said Corey Krusa, personnel director of the $4 billion-asset bank. “This isn’t going away. You need to deal with it.”

Amarillo National said employees must feel safe at work. That has meant closing a retail customer’s account when he persistently bothered a branch employee.

The customer visited the employee at the branch along with calling her, Krusa said. The employee brought the behavior to the attention of her supervisor, who immediately reported it to the personnel department, Krusa said.

While the situation was being investigated, the supervisor served that customer when he would visit the branch. The bank also asked him to use another location or work with a different employee, and despite this, he continued to harass the same female employee, Krusa said.

So the bank “fired” that customer, just like they would any employee who engaged in such behavior.

“We encourage people to come forward,” Krusa said. “We want them to have a safe and protected culture. If something was tolerated at a previous employer, it won’t be here. This is a new day and age.”

Steps like these can be important ones in eliminating sexual harassment, because it sends a message to employees that speaking up about harassment is not futile, experts said.

“I believe it is quite possible to end [sexual harassment] altogether,” Temin said. “All of the conditions are right for that to happen right now.”

Kristin Broughton contributed to this article.

(SourceMedia, the publisher of American Banker, conducted its online survey of more than 3,000 professionals across multiple industries during the first quarter of 2018. The survey is titled “Sexual Harassment in the Professional Workplace: SourceMedia Research 2018.”)