There’s a set of rules in the world of CLOs designed to keep managers’ temptations in check, so that they don’t rush foolishly into overly risky assets. But in a strange twist sparked in part by the coronavirus pandemic, these regulations are suddenly handcuffing them as they try to fend off aggressive Wall Street hedge funds.

Firms from Elliott Management Corp. to Oaktree Capital Management are increasingly profiting from restrictions on collateralized loan obligations that limit their participation in distressed situations. Some investors are even arranging deals that intentionally shift value away from the structures, according to market watchers.

The limits often prohibit CLOs from investing in highly risky assets such as defaulted debt, equity stakes in troubled companies or debtor-in-possession loans. Yet amid a wave of corporate bankruptcies triggered by the virus-induced downturn, these constraints are actually cutting into the amount of money that CLOs recoup in debt restructurings, sometimes by as much as 30 cents on the dollar relative to other creditors, according to Barclays Plc. What’s worse, short of re-writing deal documents, many in the CLO industry say there’s little they can do to fight back.

“It’s frustrating at a high level,” said Thomas Majewski, founder of Eagle Point Credit Management, which manages more than $2.5 billion. “CLOs own 60% of loans. We are supposed to be the bully, not the one being pushed around.”

Yet that’s exactly what’s happening.

CLOs, which package and sell leveraged loans into chunks of varying risk and return, are designed to attract and protect holders of the safest AAA tranches, which account for about 60% of an average deal.

As a safeguard, the structures largely restrict managers from doubling down on bets that have already gone bad, the rationale being that such wagers could jeopardize much of the capital stack while disproportionately benefiting investors in the riskiest and highest-returning part of the CLO structure -- the equity portion.

CLOs are also heavily constrained by post-crisis Volcker Rule provisions restricting Wall Street banks -- their biggest clients -- from investing in securitized loans that hold certain kinds of risky assets.

That’s left many collateral managers with little wiggle room when the borrowers in their portfolios find themselves in need of rescue financing.

New Play Book

When Elliott was negotiating with Acosta Inc. late last year to restructure its debt, the money manager - along with Oaktree, Davidson Kempner Capital Management and Nexus Capital Management - worked out a plan to slash $3 billion of obligations, virtually all of the troubled marketing firm’s long-term debt.

It was an unusual decision - bankruptcies typically don’t eliminate a firm’s debt entirely - but the thinking was it would position the company with the strongest balance sheet possible in what was a highly competitive industry, according to people familiar with the deal.

Yet it also prevented many CLOs from participating. While they’re allowed to receive equity in exchange for struggling loans in restructurings, it can be unappealing because of the impact on crucial compliance tests used to determine CLO investor payouts.

Moreover, injecting new capital generally isn’t allowed, and Acosta raised an additional $250 million via an equity rights offering. Elliott and the other investors who loaded up on Acosta’s bonds and loans as the company fell into distress also got preferential treatment in the form of exclusive rights to fund a convertible preferred equity raise, as well as additional fees.

Many CLOs likely became forced sellers, according to Gregg Jubin, a partner at Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft LLP.

“The CLO market doesn’t have an isolated instance in Acosta; others now have a play book to take advantage of their limitations,” said Jubin. “CLOs become forced sellers in the most disadvantageous time to sell because the markets know that and you aren’t going to get top dollar.”

Representatives for Elliott, Oaktree and Davidson Kempner declined to comment, while Nexus and Acosta didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

J.C. Penney, 4L

Earlier this month, private equity firm Vector Capital and hedge fund Diameter Capital Partners made a similar deal when electronics recyler 4L Holdings Corp. needed a cash infusion.

4L raised about $10 million in exchange for an 85% stake in the company. The transaction happened despite the objections of CLO managers who argued that their stock -- acquired when 4L filed for bankruptcy in December and the loans they had made were converted into shares -- would largely be wiped out since they couldn’t participate in the rights offering.

And in mid-May, J.C. Penney secured a $900 million debtor-in-possession facility split equally between new money and a roll-up of lenders’ term loans. Once again, many CLOs weren’t able to get involved, according to Barclays, with the bank estimating their recovery to be about 20 cents less than other creditors.

Representatives for Vector and 4L declined to comment, while Diameter and J.C. Penney didn’t respond to requests seeking comment.

“All CLOs to some degree have this problem, said Sean Solis, a partner at law firm Milbank LLP. “There’s a natural limit - CLOs are never going to have as much flexibility as a hedge fund, bank or private equity that can do pretty much whatever they want if it makes sense economically.”

Volcker Rule

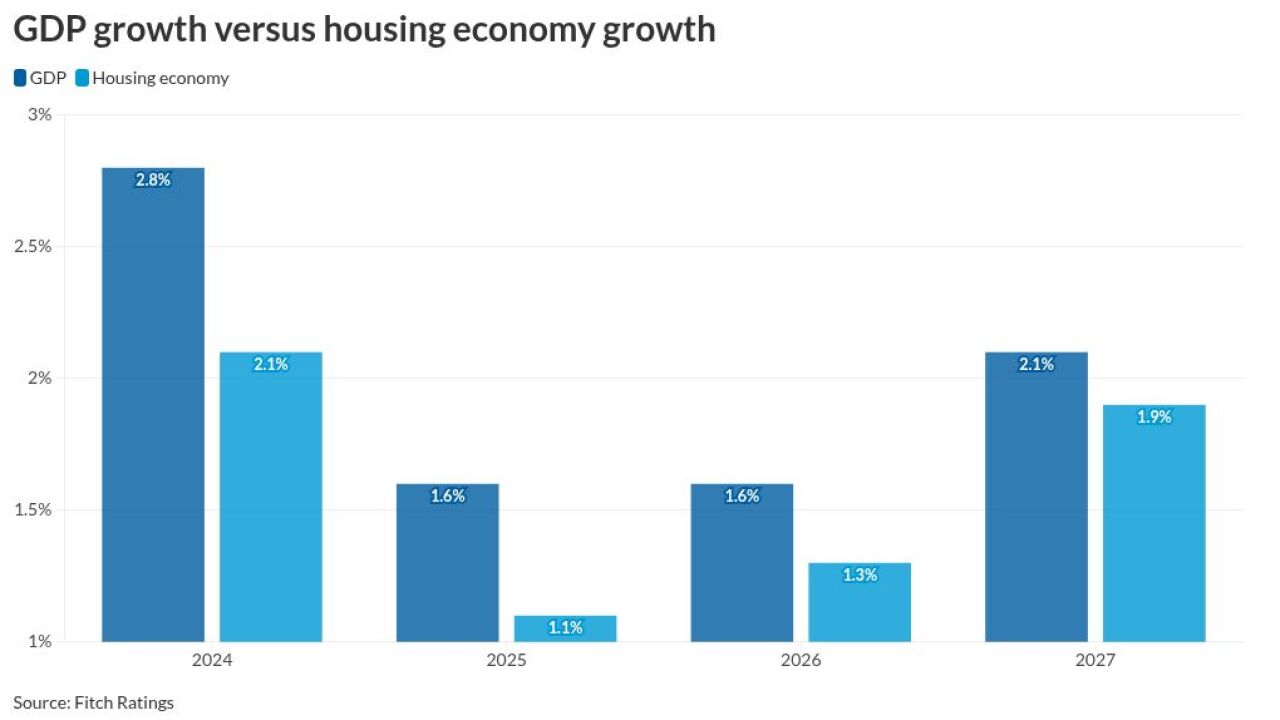

U.S. institutional term loan defaults have already reached almost $37 billion this year, and are forecast to surge to more than $200 billion by the end of 2021, according to Fitch Ratings.

Even when distressed funds aren’t actively seeking to siphon value, CLOs can find themselves hindered by their structural limitations. Before Deluxe Entertainment Services Group Inc. filed for bankruptcy last year, its CLO lenders wanted to provide more money to the ailing company. But an ill-timed credit-rating cut put the business, backed by Ron Perelman’s MacAndrews & Forbes, in the CCC tier.

CLOs have strict limits on how much of the low-rated debt they can own. The downgrade blocked many of the lenders from participating in new financing the company was seeking via a restructuring support agreement.

A representative for Deluxe declined to comment.

In recent months, some CLO mangers have inserted language into new deals that provides more flexibility to hold beaten down assets, while others have sought more leeway to participate in restructurings, according to market watchers.

An added boost could come if the Trump administration is successful in dialing back Volcker Rule provisions limiting bank investments in CLOs.

Still, it would for the most part only benefit new structures, as existing CLOs would be restricted by deal documents in line with the previous regulations.

With hedge funds piling into distressed debt as the default cycle accelerates, all signs point to strategies that shift value at the expense of CLOs growing more common. Barclays expects them to become so prevalent, it’s warning investors to start reducing expected loan recoveries when modeling CLO returns.

“CLOs aren’t meant to have creative thinking,” said Jeff Bronheim, a partner at law firm Cohen & Gresser who represents hedge funds and other alternative investment vehicles. “They are mostly designed to purchase loans and hold them to maturity.”